With film plate curved in back and lens fitted low on the front, Lawrence's camera specialized in panoramas. To photograph an entire city was a challenge in 1906.

Circa 1904. Chicago Historical Society.

The man in charge, George R. Lawrence, was anything but mad. As soon as news of the disaster had reached Chicago, he made plans to go to San Francisco with his Captive Airship and crew. With the Captive Airship he knew he could take aerial photographs of the prostrate city that no one else in the world could take. He was gambling by going to the devastated. city, but he took the chance knowing there would be an international market for his photographs if he succeeded. Lawrence was, first and foremost, a commercial photographer.

For his Chicago company he had adopted the slogan, "The Hitherto Impossible in Photography is Our Specialty." By 1906 this self-taught photographer from a northern Illinois farm had already demonstrated that his slogan was no idle boast. In 1895 his dissatisfaction with current flash guns led him to formulate brighter flash powder as well as a method for synchronizing a series of flash charges by connecting them in an electrical circuit. Five years later at the Paris Exposition he won the "Grand Prize of the World for Excellence in Photography," a distinction he achieved by building the world's largest camera to photograph a newly designed train for the Alton Railroad. The giant camera weighed fourteen hundred pounds when loaded and held glass plates eight by four-and-one-half feet. A huge contact print from one of these plates won the prize.

In his everyday business Lawrence distinguished himself from other commercial photographers by carrying out assignments using large-format cameras he built himself. With these cameras he could photograph whole banquet groups, national political conventions, and state legislatures in session. Outdoors he captured the crowds and action at baseball games, horse races, and football games. He also photographed entire industrial plants on single, large contact prints.

When hydrogen balloons proved too risky for aerial work, Lawrence turned to kites. He improved a train of Conyne kites to carry his equipment two thousand feet in the air. Here, nine kites lift a steel wire. Lengths of bamboo keep the lines from tangling. U.S. Navy, 1905. National Archives. |

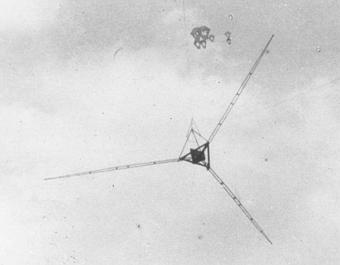

Spidery legs of the Captive Airship steadied the camera above San Francisco only weeks after the disaster. People in the streets, gazing up at this strange sight, stand fixed in Lawrence's photos. 1905, U.S. Navy. National Archives. |

In 1902 Silas J. Conyne, a Chicago inventor, patented a kite for flying advertising banners. Lawrence was impressed by its stability and lifting power, so he obtained permission to build some of these kites. Before powered flight many people around the world were experimenting with kite designs and flying techniques, and for Lawrence, kites were a useful alternative to balloons. He improved existing techniques for flying a series of kites attached by short cords to the main line. With this kite train he could hoist large panoramic cameras, as well as a stabilizing mechanism he designed, two thousand feet. Lawrence could fly as many as seventeen kites in a train, although five to ten usually sufficed.

Lawrence also devised a way to steady his cameras while making exposures. A mount hanging below the lowest kite in the series allowed him to fix the camera in any direction before sending it up. In the air, a system of booms, lines, and lead weights prevented the camera from turning horizontally while at the same time lessening the camera's tendency to swing. Lawrence solved the problem of tripping the shutter by incorporating an insulated wire into the steel kite line and using it to carry an electric current to the camera. The sum of all these parts he named the Captive Airship.

At the heart of the system were the cameras, which Lawrence built himself of wood and aluminum. The ones he designed for aerial work were modifications of two types of commercial cameras then in use. On the first, an ordinary flat-plate, fixed-focus lens camera, Lawrence replaced the usual leather bellows with a rigid box. On the second, a panoramic camera with a curved film plane, Lawrence mounted the horizontally swinging fixed-focus lens on vertical pivots. This camera covered 160 degrees in the sweep of the lens, producing extremely wide-angle photographs and unusual perspectives. Because the cameras were mounted level, they always pointed at the horizon. In order to record as much of the ground as possible, Lawrence fitted the lenses below the horizontal midlines of the film plates. Lawrence made panoramic cameras in several sizes for a variety of purposes. The one he apparently used for the San Francisco photographs weighed forty-nine pounds and held a celluloid-film plate about twenty by forty-eight inches.

In 1905 the Captive Airship came to the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt, who saw it as a possible reconnaissance tool for the army and navy. At his request, Lawrence conducted several demonstrations, including a test aboard the battleship Maine off the New England coast. In spite of initial interest, the navy never purchased a Captive Airship.

The disaster had begun with a powerful, minute-long

earthquake at 5:13 A.M. Wednesday, April 18. Almost

immediately after the main shock, fires broke out all over the

city as chimneys collapsed, electrical wires fell, gas lines

ruptured, and stoves overturned. A vivid day-by-day

account of the fire is recorded in A History of the Earthquake

and Fire in San Francisco written in 1906 by Frank W. Aitken

and Edward Hilton. They report that the last blaze was

finally extinguished on the waterfront near Telegraph Hill

on Saturday afternoon, April 21, three days after the earthquake.

In the four square miles of ruin, only a few buildings

and two small enclaves were saved. Some twenty-five

thousand buildings had been destroyed, and 438 people

had been killed.

The disaster had begun with a powerful, minute-long

earthquake at 5:13 A.M. Wednesday, April 18. Almost

immediately after the main shock, fires broke out all over the

city as chimneys collapsed, electrical wires fell, gas lines

ruptured, and stoves overturned. A vivid day-by-day

account of the fire is recorded in A History of the Earthquake

and Fire in San Francisco written in 1906 by Frank W. Aitken

and Edward Hilton. They report that the last blaze was

finally extinguished on the waterfront near Telegraph Hill

on Saturday afternoon, April 21, three days after the earthquake.

In the four square miles of ruin, only a few buildings

and two small enclaves were saved. Some twenty-five

thousand buildings had been destroyed, and 438 people

had been killed.

When George Lawrence arrived a few weeks later, he and his crew prepared to photograph the burned area from several locations and altitudes. Working in San Francisco during May of 1906 must have been difficult, but Lawrence succeeded in making four photographs, copies of which survive in the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress.

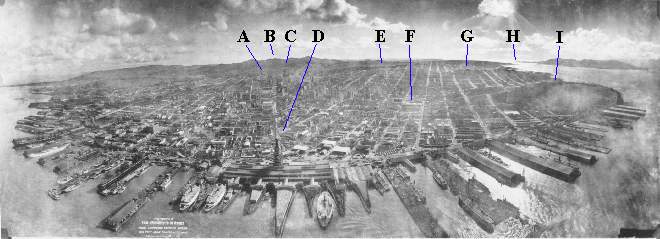

Lawrence's photographs have an unusual perspective because the film was fitted over a curved plane. When we view a flat print made from the curved negative, the areas directly in front of the camera appear the largest and most detailed, while those at either side seem to fall away in the distance. The scene is convex, bulging toward the camera. The streets in the foreground are actually straight, but in a cylindrical-plate photograph they seem to curve.

The extremely wide angle is another distinctive characteristic of Lawrence's photographs. As far as we know, Lawrence never wrote a description of the Captive Airship and camera, so to determine the angles of view I checked features in the photographs against maps of San Francisco at several scales as well as reports and books showing buildings and their locations. I thus deduced the approximate camera positions and view angles of the four photographs of the burned area. With the exception of one photograph, the average view angle is about 130 degrees.

Surviving landmarks attest that the scorched blocks in the photographs were indeed San Francisco. Numbered points show the camera positions and angles of the four views. Adapted by the author from U.S.G.S. Bulletin #324, 1907. |

The huge size of the photographs made a great impression on viewers then, just as it does today. Three of the four prints average forty-seven inches by nineteen inches. Lawrence, it must be emphasized, did not produce these big photographs with an enlarger; they are contact prints. Each one invites close inspection of its details: people in the streets, horses, wagons, tents, piles of rubble, and remains of buildings. Everything but the horizon is in sharp focus.

The copies reproduced here are meager representations when we consider the richness of the large originals. In them we see people going about their business in the streets or looking up at the Captive Airship; horses and wagons stand amidst piles of rubble; neat rows of tents shelter the homeless. All the details of a stricken city slowly returning to normal life are clearly visible. The prints record a landscape of destruction not seen again until World War II, when aerial views of bombed and burned cities were widely reproduced.

The memory of George R. Lawrence and his work has faded since his death in 1938, and little has been written about him. In the first decade of this century he stood alone in the quality and innovation of his work. No other kite or balloon photographer produced images like those he made routinely. A master of photography who combined technology with his own ideas to produce the prints shown here, George R. Lawrence remains an American original.

This novel aerial perspective drew world attention. Flown two thousand feet above the bay, the lens scanned the waterfront. Beyond are A) the Call Building, B) Twin Peaks, C) City Hall, D) the Union Ferry Building, E) the Fairmont Hotel, F) the Appraiser's Warehouse enclave, G) Russian Hill, H) the Golden Gate, I) Telegraph Hill. G. R. Lawrence, 1906. Library of Congress. For an extremely high-resolution version of this image, click here: 11709 x 44716 pixels (20 Mb). |

FURTHER READING

Frank W. Aitken and Edward Hilton. A History of the Earthquake and Fire in San Francisco. San Francisco: Edward Hilton Co., 1906.

W. H. G. Bullard, A. L. Willard, and J. H. Holden. Report to the Commander in Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet. 12 January 1906, Record Group 74, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

L. H. Chandler. Report to the Chief of Bureau of Ordnance, U.S. Navy. 22 May 1905, Record Group 74, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

David Starr Jordan, ed. The California Earthquake of 1906. San Francisco: A. M. Robertson, 1907.

"George R. Lawrence, Biography." Encyclopedia of Photography. New York: Greystone Press, 1974

Beaumont Newhall. Airborne Camera. New York: Hastings House, 1969.

"The '02 Version of the U-2." National Photographer, August 1969, pp. 417-19.

H. H. Slawson. "$15,000 Photograph." Popular Photography, March 1939, pp. 30-31.

"Kite and Balloon Photography." Encyclopedia of Photography. New York: Greystone Press, 1974.

U.S. Geological Survey. The San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of April 18, 1906 and Their Effects on Structures and Structural Materials. Bulletin no. 324. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1907.