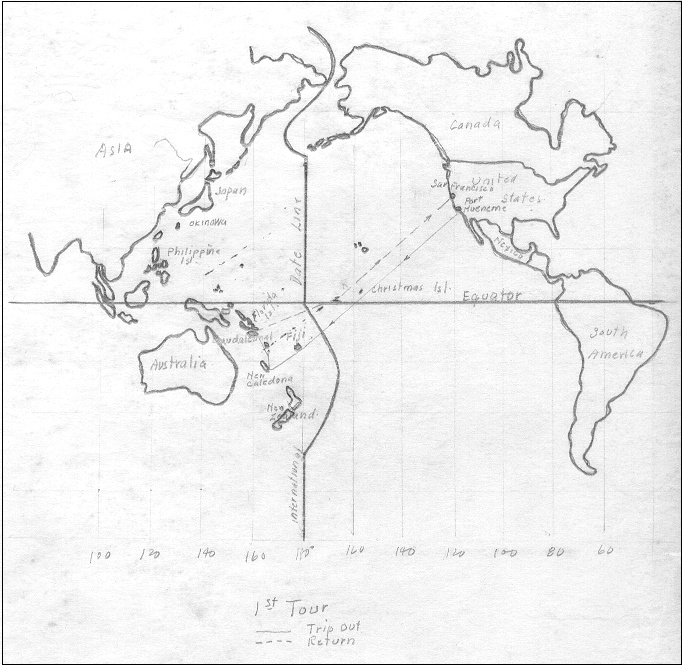

Water, water and more water, and two little ships following one another like two little ducks a pond. You know, a 10,000 ton freighter is quite a large object as she lays alongside the dock. And when one sees the enormous amount of material that can be stowed therein, it seems to get bigger and bigger. But as you sail out into the vast expanse of the oceans, the ship shrinks and shrinks, until it seems like a minute part of it's surroundings. Our course was set West-Southwest and for the first few days we kept busy getting used to our new surroundings and exploring the various departments of the ship.

The Alcoa Pennant was a nice neat little ship, only about a year old, and was built for a combination passenger and freighter. We had an old "Swede" for a captain, and another old "Salt" for a first mate. The crew members were civilian merchant marine.

The Island Mail was the lead ship, and as she was a much faster ship, she really kept her distance most of the time. There being only three officers aboard our ship, we were kept quite busy. We had to keep a log of the trip, also stand watches as required by the Captain. We were kept well informed of all details of the trip, in as much as we were expected to do our definite part in case of trouble. This is the reverse of the procedure on a troop carrier, where only information that immediately affects the personnel is allowed to leak out. This is to prevent any danger due to mass fear or misunderstanding. So when I speak of some of the dangers and etc. during the voyage, it is entirely possible that the bulk of the personnel aboard the troop ship were entirely unaware of them.

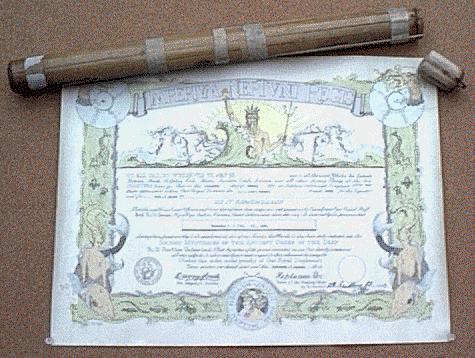

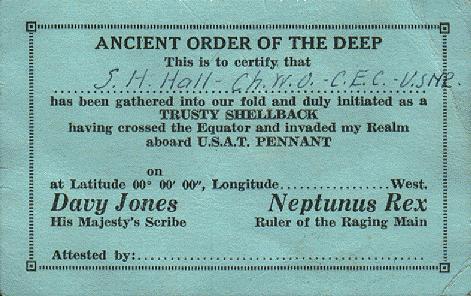

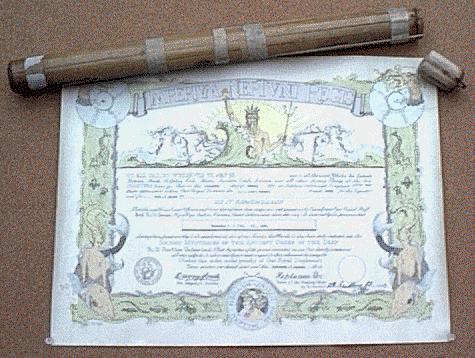

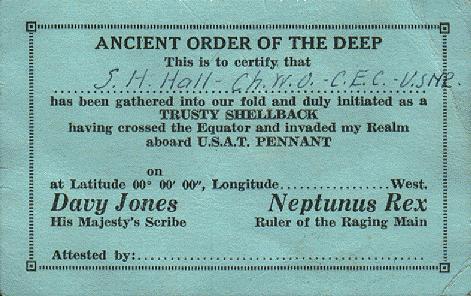

The start of the voyage was made without escort, and proved to be uneventful except for a few pleasant incidents, such as the crossing of the Equator and the ceremonies incident to the event. All who had not crossed the line before were put through a regular initiation ceremony, and in as much as there were no women aboard, and the class of men making up the crew, you can imagine that it was a pretty rough affair. From Captain on down, all took part in the ceremony. I went through with the rest and received my degree of Shellback. A beautiful piece of paper with the Captain's signature affixed thereto. For the next few weeks my bald head was quite in style and matched closely the great majority of close cropped heads aboard.

Then we approached Samoa, and came into view of the first land that we had seen since leaving the states. We expected to pick up our convoy here and possibly drop anchor for a few days. But neither happened, for as we approached the Naval Base there we were advised that we had missed our convoy by a couple of days and we were ordered to about face and proceed on our course alone.

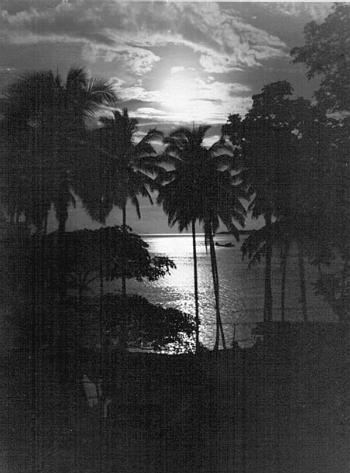

But we did see a most gorgeous sunset here. This particular place is noted for the colorings of the sky at sunrise and sunset. As the sun sank beneath the water on the horizon that evening, the coloring was fantastic, just beyond belief. The sky changed from the clear blue of day, through deep blues and pastel tints to gold, and then to bright orange and deeper and deeper until it shed a blood red light over all. Then as the sun disappeared, quickly faded into the black of a tropical night, with the blackness overhead studded with bright jewel-like stars. The water, which was as calm as any lake on a still clear day, took on the most unbelievable colors. For a little while it was cocoa colored all flecked with gold and black splotches. The gold flashing in the rays of the setting sun like millions of jewels scattered about. It was simply an indescribable sight and far beyond any human artists' efforts. The wildest colors he could have imagined would be tame in comparison. The islands stood out in silhouette in the background, with the palm fronds lining the profile. It's a memory I shall never forget.

So on we went again, out into that mighty expanse of space. Of course at night everything was blacked out completely. All port holes were closed and covered with steel and curtains. All doorways were covered with two sets of heavy curtains, weighted to keep them from blowing open. As you can imagine it was hot as purgatory all night long inside the ship. And some of the nights were mighty black. It was a strange feeling to be outside on these black nights and to be running without any lights whatsoever. The blackness seemed to wrap around one like a blanket and always left you with a sense of danger, like a blind man moving into unknown territory. When on watch I always felt as though another ship might suddenly come up in front of us and we would not be able to see it in time to clear. But although this was always a real danger, our course had been plotted so that we were not likely to meet any other ships. We were never on any of the regular ship lanes. And only once did we meet or see any other ship and that did happen at night, and it came uncomfortably close. All hands jumped to their gun posts on first sighting it in the dark and things were pretty tense for a while as it slid noiselessly by us in the darkness, like some evil shadow. We never did find out that ship it was, as we were not scheduled to meet any. And I suppose that aboard the other ship things were alert and tense too until we had passed.

We had marvelous weather for practically the whole trip. Most of the time the sea was perfectly calm with gentle swells. Sometimes we would run through rain squalls of short duration, but nothing like a storm. It was interesting to note how many rain squalls we could see and pass by some days without getting into any of them. I have counted as many as six at one time though for the whole time the ship was riding in the bright tropical sunshine.

We also found that flying fishes were not a myth after all and we spent many happy moments watching them. As the ship would plough into a big school of these interesting creatures, they would rise out of the water like spray and glide out of the path of the ship. They would rise some five or six feet out of the water and gracefully glide over the waves some three or four hundred yards then plunge with a splash into the side of an oncoming swell. Many times we would find specimens among the deck cargo, apparently where they had landed at night in confusion and possibly getting started off in the wrong direction. Some of these specimens would be 12" or 14" long.

Also sighted one school of a half dozen whales, which we followed with our binoculars for quite a while. Quite often porpoises would play around and follow the ship. Twice we spotted huge tiger sharks following alongside the ship. We were not allowed to throw any kind of refuse overboard due to the possibility of making a trail for submarines to follow. Once a day just at dusk all garbage was dumped over the side. These tiger sharks, we were informed, had become very numerous of late, especially in or near areas where naval engagements had taken place, and where many bodies and much blood had gone overboard. Some of these sharks were huge specimens, seemingly 18 or 20 feet in length, and they seemed to glide through the water with the utmost ease.

I recall at one port, while we were anchored, a few of us decided to while away some time fishing. We had passed through huge schools of fish in the area, and often you could even see them in the clear water next to the ship. We had good luck getting fish hooked, but only succeeded in getting one fish aboard whole. A grand specimen too, some 25 pounds in weight. The sharks would take over half of the fish before you could haul the fish in. It gave you an odd feeling to be pulling in fish heads, for that was about all that you had left. I soon got disgusted and left the group. Later some of the boys tried to catch some of the sharks, but had no luck. But when we gathered all the fish parts together, and pitched them overboard, they thrashed the water fighting for them. Boy, they were ugly customers and I have no desire to be in the water with them.

We also passed within sight of one waterspout. We followed it through our binoculars and were glad that it did not turn and come our way. The Captain informed us that they were quite numerous in those particular parts and though small could do a great amount of damage if you should happen to get in it's path. It appeared like a huge flexible gray column between a black cloud above and a black spot on the sea below. Through the binoculars it looked real wicked and the sea at the base of the column seemed to be churned and angry.

And so the days passed by, sometimes they seemed endless. We officers really traveled in style during this period, as the Captain considered us as naval passengers unless we were needed in an emergency.

We ate well, at a table of our own, slept as well as possible under the conditions, and did about as we pleased so long as we finished the few little tasks that were assigned to us by our Commanding Officer. So far we did not even have to stand watches.

I shall never forget the tenseness and excitement as we sighted our first planes. We were about two days out of Noumea in New Caledonia when an alert was sounded. Three planes were sighted on the horizon, but they did not come in. All hands were standing by their guns, but the planes swung about and disappeared over the horizon again. We waited for them to return but they never did. Little did we know what that was to mean a little later on. Then early next morning the alert sounded again and two more planes came up over the horizon. But these came on in and circled around us,and you can imagine our joy in identifying them as our own. Two Grumman Wildcats had come out to escort us in to Noumea. Later on two PBY's joined in and how much relieved we all did feel. We came into Noumea Harbor about mid-afternoon and anchored. Were we surprised to see all of the ships there too. We counted some 38 freighters besides all the other type of craft. At that time that seemed like a lot of ships, for we had very few freighters. Later we were to see hundreds of ships in a harbor and never think a thing of it. It was January 26th when we anchored in Dumbea Harbor, Noumea, New Caledonia.

|

We stayed here for a few days while we unloaded some equipment for one of the C.B. Battalions already stationed there. I visited the town of Noumea twice and found it to be a small but quaint little French town. Of course everywhere were marines and soldiers, both American and French. All the little stores and shops were doing a thriving business if they had anything to sell. But stocks were being fast depleted. One little bit of a place seemed to always be full. It was a little pastry shop and they made the most delicious French pastries. We bought a nice big supply to take back to the ship with us. They were surely delicious too.

Fortifications and barrage balloons were everywhere, for at this time this was not far from the front and was the main supply source. The residential section of Noumea was fairly nice though small and was pretty well overgrown and dilapidated. Most of the French had left for the War or the mainland. Only a handful of real French were left. The bulk of the people there were half caste, of all types. Some of them were real good looking according to our standards. Mixtures of French and Native Blacks were most prevalent, but there were also many Oriental and Black.

But the Town and it's environs were literally swamped with our soldiers and the town itself was all but taken over by them. We picked up a few souvenirs here but due to censorship regulations we were not allowed to send any home.

On Monday 1st February 1943 we left New Caledonia in convoy. We picked up two other freighters and a tanker and were convoyed by two large destroyers, the Hopkins (our flagship) and the Pathfinder. Also one small destroyer the Skylark and a corvette (converted yacht). We headed out to sea, the ships in single file, with the four convoy ships out to either side of us about a half mile or so. The Alcoa Pennant was the last ship in line and on our starboard was the corvette and on our port was the Skylark. The two large destroyers were abreast the forward ship in the line.

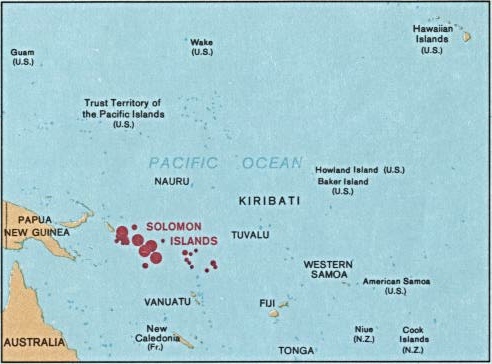

Editor: Modern day map of the area, the Solomon Islands are highlighted as they would be too small to see otherwise. |

We were now in really "Hot" waters and all of us were on watches, four hours on and eight hours off. My post was on the Captain's Bridge, from 800 to 1200 and 2000 to 2400 hours. The sea still remained quite calm and the nights were really gorgeous, especially on a dark night. The canopy of bright stars overhead, and sometimes the reflection of the stars in the quiet waters started at your feet and carried right on up overhead. Made you feel as though you were suspended in space.

Things went along pretty well for a few days. Then one day we faintly heard the rumble of guns in the distance, and word was signaled back that a sea battle was in progress ahead. Soon afterward we had our first submarine alert, and were advised of a pack of subs being detected in the vicinity. About an hour later subs were detected in three directions. We received a message from our flagship to take cover in the harbor of a nearby island. Immediately we changed course and just before nightfall we came into sight of the New Hebrides. We sailed slowly into Havannah Harbor in the island of Efate of the New Hebrides on Thursday, 4th February 1943. This was a beautiful harbor completely surrounded by steep high cliffs and mountains.

A strange sight greeted us as we entered the harbor. The water was completely covered with jellyfish of all sizes and shapes and many colors. The ships literally plowed through a sea of jellyfish.

We stayed here until the next day, when we received orders to proceed. Soon we were on our way again. It was not long before we were alerted for subs. All watches were doubled. This meant four hours on and four hours off for all of us officers on the Alcoa Pennant. From reports some six Subs were reported and on the next day we were again heading for harbor and safety. This time we put into Segundo Channel, leading into the harbor at Espiritu Santo in the northernmost part of the New Hebrides. The channel is quite narrow and some seventeen miles in length and leads into the harbor proper, which is very large. All other entrances to the harbor had been closed by nets and mined. Coral reefs were all about us, and as it was late when we came into the channel our Captain decided against attempting to make the channel after dark, so we dropped anchor off to one side after entering the channel. Two of our destroyers rode ahead through the channel to cover the convoy on entering the harbor. The two smaller craft stayed outside at the entrance to the channel so as to cover the approach. The channel had quite a reputation and only a week previous a troop ship had been torpedoed right at the entrance to the harbor and so great precautions were taken.

It is interesting to speculate now on the fact that we had ten tons of dynamite stored aboard as part of our cargo. But no damage except slight shaft alley leaks were found. We surely were relieved when we rounded the turn a few minutes later and entered the safety of the harbor. We were puzzled for awhile as to why the mines had gone off, as we had not passed close enough to detonate them. But we soon found out from the Port Director who came aboard shortly after we entered the harbor. As he said when questioned, "Only two things I know that could set of those mines, a whale or a sub, and I ain't seen a whale in here for years." Navy crews were immediately dispatched to the scene to investigate and replace the mines. A sub had apparently trailed us into the channel, as was done the week before, and swung out at that particular widened spot to get us broadside with their torpedoes. But the mines went off first, praise the Lord, and you can imagine my feelings as I heard the news. We were also informed that those two mines were new ones, placed there after last week's tragedy. It sort of made you feel small and lonely. A few days later as we again passed the spot on our way out I actually felt cold as I noted the ships cut through quite an oil slick that had formed.

We entered Espiritu Santo harbor on Feb. 6th and stayed there a few days while ships and planes hunted around the waters over our route. Espiritu Santo was one beautiful spot. The green and tropical foliage with the palm trees and palm fringed drives making a beautiful picture. We had two nice swimming trips here, going up a little river nearby in a personnel boat to a special swimming hole where the water was sheltered and the bottom covered with smooth gravel. And my oh me did that water feel good, for it was necessary to be very conservative with water aboard ship. And this little stream we found was literally filled up with Marines. The whole area was loaded down with soldiers and Marines. They were all well hidden in the dense foliage and were not visible off shore or from the air either I imagine. But when we entered the little stream it made you think of Coney Island. Looked like Marines were everywhere. Hundreds of them stripped and in the water, other hundreds camped all along the shores of the stream. We had to literally push our way through the throngs of swimmers and went on inland a ways, to a little island where we could beach our boat and be out of the way. These days were greatly enjoyed and appreciated after such a long time of being cooped up on a ship. But it was of such a short duration.

On Tuesday Feb. 9th we hoisted anchor and following our destroyers lead we sailed out into the channel leading to the sea. We picked up our other escort ships at the mouth of the channel and getting into our regular convoy positions we started out on our journey once more. Sailing in convoy under the then existing conditions was not especially pleasant. We must follow a zig-zag course all during the daylight hours and sometimes the patterns we followed were really complicated. They surely must have been a headache to the navigator, who was responsible for keeping us on course.

We had not gone more than a day out of Espiritu Santo before we had again picked up our sub pack. But this time there were no nearby islands for a haven of safety. So one day after we had been alerted a message came back from the flagship, "sub off port. Skylark attempt contact same." So the next thing we knew the little destroyer suddenly came to life, spurted forward and with the foam curling from her bow, made a graceful turn and started off towards the horizon. All hands were quite tense as we watched her progress attentively and realized the danger that she was deliberately running into. Soon she became quite small to the naked eye. But the Mate on watch and myself continued to watch her through our binoculars. She seemed to have changed course and to be running in a large circle, and huge geysers of water were spouting up astern as she dropped her depth charges. Suddenly it looked as tho the little destroyer were afire. I inquiringly turned to the Mate, who just said "gunfire".

Yes, she had surfaced her quarry and was pouring everything she had into the sub as it appeared. Minutes later the dull "WHUMP" of the depth charges just became audible and by listening carefully we could just make out the rumble of the gunfire. After cruising about a bit until she had dropped almost out of sight the little destroyer started coming in. As we watched her, with real pride in our hearts, when about half way back suddenly she changed her course and swung into a circle again and the water spouts again shot up at her stern. The deep "WHUMPS" were distinctly audible this time as she completed a full circle. Again she cruised around and waited. This time she waited so long that she had fallen back to the horizon again before she started coming in, her mission accomplished. She had no sooner takes her place in the convoy, when the corvette on the opposite side took off toward the horizon, and soon disappeared. It was quite dark before she appeared again and quietly took her place in the convoy. The all clear sounded shortly afterward and we all went below with a feeling of gratitude in our hearts for the little escort ships.

I for one, had developed a great respect for these so called "tin cans" and their crews. They are truly the "bull dogs" of the Navy and though not so spectacular and not much in the news, they truly play a most vital part. To waltz right out and tackle an enemy you can not see and one who could blast you clear out of the water with one chance shot, takes guts and courage of the highest sort. Whether subs, planes or ships, they are always out front mixing in and stirring up the enemy so that the Big Boys can get better chances to pick them off. The "Watch Dogs" of the service, whether it be a freight convoy, fighting unit, or a land base. So my Hats off to the "tin cans" and their crews.

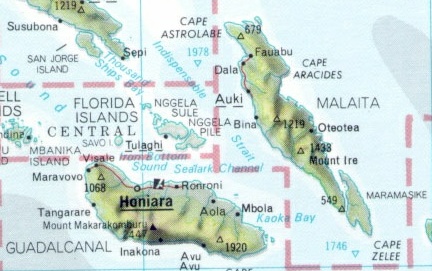

Next morning early we were alerted, and the "Pathfinder" was ordered out. We watched her as she gracefully though speedily moved out. She disappeared over the horizon and was not seen again until some three of four hours later when she slipped again into her position, like a huge cat licking its chops after a meal. Some days later, we got the score: four subs to our convoy's credit. For a few days after this things quieted down and the alerts stopped. Then one day as we approached the Solomon Islands we were ordered to circle due to danger ahead. We were just about to enter the channel through the reefs leading to Guadalcanal and the surrounding area. This is a very narrow channel, shown on the map as about 150 yards in width. The battle of Guadalcanal had been at white heat and the Navy had dispersed a large Jap naval force at Cape Esperance. Some ships and subs had escaped and were believed to be in the channel. So we went round and round all afternoon as PBY's and destroyers combed the channel.

Late that evening we were ordered to form convoy again and "Move forward in single file - each ship directly behind ship ahead". This order impressed me inasmuch as it seemed unusually long and detailed. As a rule, "proceed on course" would have been sufficient. So on a dark night, with a slight haze in the air we went forward. I went on watch as usual, at 2000 and it was so dark that it was difficult to see at all. I could just make out the ship ahead as an extra dark spot. I noticed that we were not exactly in line with the ship ahead, but were in our usual place. The Captain always kept quite a bit to the starboard of the ship he was following. The unusual message that we had received that evening kept coming to my mind, so I mentioned the fact that we were out of line to the mate on watch with me. He resented very much my intruding in his business and said so, so I dropped the subject. About 2300 I noticed in the darkness a small object coming towards us and soon after a few small ships passed close by on our starboard. Then as I strained to pick out the ship ahead of us, a huge black shadow loomed up, seemingly directly in front of us. I yelled to the mate and the helmsman put over hard to port, but almost in less time than it takes to tell of it, a huge tanker came up out of the blackness, just off our starboard bow. It swept past us and how it failed to take us with it no one will ever know.

It brushed so close that it cut the painter and scraped the paint off of one of the life boats that were left hanging over the side in case of emergency. As the tanker passed, I noticed an Officer on the bridge with his mouth wide open and holding hard to the rail, as though waiting for the crash. As the danger passed and we came out unscathed, I looked ahead and noticed that we were still out of line to the starboard. I suppose I must have made some sarcastic remark to the mate, but he never said a word.

But before my watch was up I did notice that we had moved over directly in line. My watch was soon up and I was glad to go below and try to relax. I understand we passed several other ships before morning. Apparently under cover of darkness they were moving convoys both ways through the narrow channel and thus the detailed order.

We Reach our Destination: Gavutu

Early next morning I came topside. It was a beautiful and clear morning and we had passed the channel and in regular convoy formation. Pretty soon three of the ships and two of the destroyers pulled away and left the convoy, heading for Gaudalcanal. Our two ships and the other two destroyers proceeded on north to Florida Island where we were informed that we were to land. Gavutu and Tulagi, neighboring islands, had been taken shortly before and another C.B. Unit was busy as bees cleaning things up and making the place liveable.

Gavutu was a sentinel island for the approach to Tulagi and it had been shelled and dive bombed until it was a sight to see. It was a small round island and a high hill made it cone-shaped. The Japs had dug into this hill and hollowed it out until it was a huge cave for storage of stores and ammunition. Near the cave entrance were two six-inch navy guns and all around the hill were gun emplacements and machine gun nests. Our Marines in their original assault here were cruelly beaten back by this island's defences, so the Navy brought up ships and planes and stood off shore and shelled and dive bombed it. The trees were cut off as though a giant pair of scissors had been used on them. The path of the shells was also visible on the mainland of Florida Island proper some three miles back of Gavutu, where a regular swath was noticeable in the thick jungle growth.

Editor: Modern day map of Guadalcanal and the Florida Islands (now known as Ngella Sule and Ngella Pile). Gavutu is just to the East of Tulagi, too small to see. |

As we passed this island it was a sad looking sight, and not exactly sweet smelling. It gave us our first real glimpse of the real ravages of war. We slipped into our berth about a mile off shore, and dropped anchor on l2th Feb. 1943.

Gavutu lay about 3/4 of a mile off to one side while Florida, our objective, lay about a mile on the other side of us. The ships must first be unloaded on to lighters or barges, which had to first be built, and then taken to shore and handled again. Of course we had rehearsed this procedure many times on the way over, but now the time had come to put our ideas into practice. Soon after dropping anchor I received orders from our C.O. to remain aboard and look after the unloading of the ship. Then started the first real strenuous days and they were to last for months to come. The Navy assigned two LCT's to us for the first week, giving us a chance to build our pontoon barges. Also the boys on Tulagi sent over a couple of old barges to help out. Our C.O. was very anxious to make a record of unloading the ship so he planned on around the clock work. This proved quite an error in judgment and we were to pay dearly for it a little later on. The Marines and Air Corps boys told us we were crazy to attempt such a thing. But we started out with a bang, two crews working 12 hours a day. Although the weather was warm, it rained incessantly. Not just a little, but regular deluges, such as we had never seen before. Our C.O. and a party went ashore for reconnaissance and soon materials were moving ashore in a steady stream.

We were the first white people to set foot on this island, with the exception of a stray missionary. This was the territory of the famed head hunters of the South Seas. Also just prior to the Tulagi Battle a small group of fliers had sneaked in and hidden among the foliage and did reconnaisence work for the Marines. Some of these were still there and glad to be able to come out of hiding. The spot picked for our landing showed on our brief maps as a sandy beach. Instead of being sand it was coral and all around the area were treacherous reefs that even the personnel boats would hang on. Furthermore the one small bit of shore that was available was surrounded by a strip of swamp averaging some 100 yards in width. The beach itself was not more than 200 yards long and the dry ground back of it was only about a 150 to 200 hundred feet wide. Then came the swamp strip. Getting across this morass to the higher ground beyond was our first stumbling block.

The first Cat (Caterpillar tractor) that hit this swamp dropped nearly out of sight and liked to have scared the operator to death. But by cutting trees and dragging logs in and sinking them in the mud we finally got passage for the Cats to the main ground beyond. But materials and equipment were coming ashore faster than we could get them across the swamp. So besides sheltering the Battalion personnel the little strip of beach ground was accumulating a huge mass of materials awaiting transportation across the swamp. The men were living on the little beach strip further up the shore under whatever shelter they could find, as the tents were not all ashore. The jungle was so thick one had to actually hack a space out with machettes to put up a tent. Many of the boys just set up their cots and would fall down on them in their wet soggy clothes and fall asleep with the rain pattering down on them as they lay exhausted.

Everywhere was mud, and more mud, and the more we worked

the worse the mud. Storm clothes were a nuisance and were

discarded by most of us. If they kept off the rain, they made you

sweat so that you were soaking wet anyway and they did not help

the mud. It finally got to the point where trucks would sink

and turn over and about the only thing that could navigate the

stretch were the Cats and equipment with caterpillar treads. We

found no rock on the island and finally went to the shore and

shoveled out coral. So things went for the first few days. We were

so busy and worked so many hours and plowed through so much

mud that life seemed to be all aching bones and mud, Mud, MUD.

Then came February 22, Washington's birthday to you, but to us

a nightmare never to be forgotten.

Shortly before 100 on that fatal day, a Jap bomber slipped in, flying so low that the radar on Guadalcanal (the only one in operation at the time) failed to pick him up. He apparently had seen our lights from a distance and used them as his target and believe me he DID NOT MISS. He dropped his load of bombs squarely across our camp site. From the craters that we afterward noted they must of have been of the 250 pound demolition type, six in all being dropped. The first one landed among a large supply of loose pontoons that we had tied together on the beach. Another fell in a ditch quite close to a little bridge we had built to help take the water away from the roadway we had built across the swamp. A third fell squarely in the middle of our supply dump. A fourth dropped at the edge of the swamp just missing a group of headquarters company tents. The other two dropped harmlessly in the jungle beyond our area, one leaving quite a large crater.

It all happened so quickly, without warning that the actual time was only a fraction of the time that it takes to tell it. The lights went out and the roar of the bombs and a blinding flash came next, then after a very brief period of quiet, apparently from shock, all Hell seemed to break loose and pandemonium reigned. The supply dump caught fire and set off an ammunition dump next to it. The flames leapt for a couple of hundred feet into the air, dwarfing the tall stately palms that were seemingly holding their fronds so proudly some 8o feet or more in the air. The ammunition began going off and 40 MM anti-aircraft shells started whizzing in all directions leaving weird tracer trails as they flew off into the jungle. I had just completed my shift a bit past midnight and was just about to go below when the first detonations came and the flames leaped high in the air.

Immediately sensing what had happened, myself and a few others standing by jumped aboard the personnel boat which had just unloaded the new shift of working crews and made our way to shore to help in any way that we could. In the excitement of the moment, to this day I have no idea of who or how many came ashore, or which boat brought us in. I think the main idea in the most of the minds of those who could still think clearly, was the fact that the brilliance of the fire was a regular beacon to guide other bombers to the scene. And all through the balance of that awful night we were definitely expecting more. In the maddening fear and excitement immediately following the explosions, especially as the ammunition started going off, about half the men and officers took to the jungle. We had not taken any time to build fox holes and the only available ones were a few left by the Japs as they moved inland upon our arrival. These were soon filled to overflowing, and the balance of the men figured the jungle was safer than the vicinity near by.

No fire equipment had as yet come ashore and a neighboring battalion who saw and realized our plight saved the day by rushing a barge load of fire pumps to our aid. The confusion and horror of the following hours can not be described, even details and people being all confused and jumbled in one's mind. Two individuals stand out definitely in my memory on that fatal night. Lt. White, a vet of the first world war, as he earnestly and frantically tried to get some order out of the chaos and systematically fight the fire. And Chief Irwin, another older man, and also a vet of the first war. I seem to see him flying up and down the beach, smoke and shells flying all around him. Helping to push or pull fire equipment, rushing someone or something here or there. I can still hear Lt. White's voice as he would yell to the Chief to keep the Hell out of some place or other. Later when Chief Irwin had a chance to take stock of himself, he found his shirt actually in tatters from shrapnel and bullets and he had two places on his body where he had burns, apparently from bullets. We counted nearly a hundred holes in his shirt, believe it or not, and his cap was all but annihilated. He later sent these two items home to his wife as souvenirs.

Yes, these two men stood above all others in that emergency. Another hero of the hour was a little corpsman, who held a mattress up in front of himself and crawled toward the burning ammunition dump and pulled a wounded buddy back to safety. For this deed he received a special citation, and it was well deserved.

The details of that night are too horrible to print. Sufficient it is to give one or two incidents to illustrate the queer quirks of the hand of fate in times like these. Three men asleep in one pyramid tent. One mans body was found on the cot as he lay asleep, the head completely decapitated by a large piece of steel from one of the pontoons and lying by itself in another part of the tent. On the cot next the body of another was found half on and half off the cot, just as though he was in the act of arising from his sleep. The man of the third cot was blown completely out of the tent by the concussion and quickly arose and ran to safety without getting a scratch.

The Medical Officers surely deserve a word of praise too. An emergency operating room was quickly made up in a large tent that had been erected for supplies. Oil Drums with boards laid across them served as operating tables. Emergency lights were fixed up inside the tent and four doctors operated steadily until the wee hours of dawn. There were some fifty casualties by next morning. Six of these dead and some 26 or more who were so badly wounded that they were put on board ships for transportation back to the base hospital. Of these some dozen or so came back to the battalion some six or eight months later. The balance I never heard of any more.

All the rest of the night we worked feverishly trying to extinguish the fire and expected momentarily to be visited by the bombers. But morning came at last and no more enemy planes appeared. We found out later that one of the few fighter planes then on Gaudalcanal, being used for patrol, had seen the flash in the sky and moved off his route to investigate. He, fortunately for us, intercepted the bomber coming out and shot it down. Otherwise we could easily have been wiped off the map in short order. Such is life in war and surely a greater power than man is guiding the hands of Fate. One thing we really learned and that was no more work after dark. To observe a strict Blackout. After this when it got dark it was DARK. Even a lighted cigarette was apt to bring on loud curses and a fusillade of shots from the men.

A beautiful view of our original landing spot. |

But by daylight the fire had been brought under control and we had an opportunity to see the results. It was an appalling sight. All the small arms ammunition, all our extra rifles and arms, most of our small store and clothing supplies, about half of our tents and all of our sand bags and etc. were gone; vanished in smoke. Then we got another shock, for there, about 150 feet from where the ammunition was burning was a huge stack of some 2000 drums of aviation gasoline hidden in the jungle. How it came through undamaged no one will ever know, and if it had caught fire, just the thought of the horrible results made you shudder. So score No. 2 for the hand of fate and our Guardian Angel for that night.

It was about two days before we were able to get a complete muster of the men. Some of them got lost in the jungles and had a time finding their way back to camp. But work proceeded as usual next day. That day was highlighted by the gruesome work of preparing the bodies of the dead. These were carefully assembled and sewed up in canvas, secured by ripping up some damaged tents. These canvas-shrouded bodies reminded one vividly of Egyptian mummies. Then rough boxes were made of salvaged lumber and these canvas wrapped bodies placed therein. Special funeral services were held at high noon and the bodies were placed aboard an LCT for transportation to Tulagi, where they were held for burial in the cemetery just being prepared there.

Some of the effects of these demolition bombs were strange to see. One bomb fell among the pontoons we had stored on the shore with devastating effect. Some dozen of these pontoons were an entire loss due to being twisted and filled with holes. One must realize too that these pontoons are built of 1/4" steel plate, solidly and tightly welded to heavy angle iron frames. They are five feet by five feet by seven feet in length and weigh over 2200 pounds apiece. So from this you can imagine the destructive power of these bombs. Three of these pontoons had entirely all of the plate ripped off. We found these three blackened and twisted frames submerged in the water. Pieces of these pontoons were later found in the strangest places. A few months later while clearing a portion of the jungle for the Officers Mess building we found a tree with a piece of pontoon over a foot square,wedged clear through the trunk of the tree. This tree was some three quarters of a mile inland from the beach.

ON OUR OWN

In about 30 days we had our ships unloaded and one really got a funny feeling and a big lump came into your throat as you watched the last ship pull away and disappear over the horizon. Now we were really on our own. But with the vast amount of work to be done, the continual rain and the frequent air alerts,we did not have much time for retrospect.

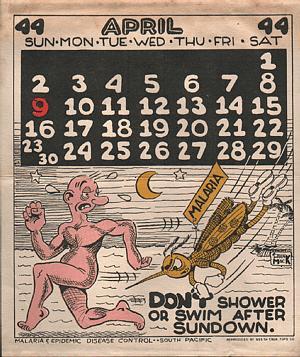

Malaria was one of the biggest enemies we had to fight. This became a major factor in our site due to the extreme swampiness of the terrain. Soon after landing our C.O.came down with Malaria and he had quite a fight with it for most of the time he was overseas. There was a period when nearly half of the battalion was incapacitated due to Malaria. The island was put "Out of Bounds" for a month or more the first Spring. The swamps and the continual rains made it almost impossible to get any permanency to the roadways and our trucks and equipment were not of the type for use in the extreme mud conditions that we encountered. We were supposedly landing at the end of the rainy season, but there actually seemed to be no end. We continuously fought the rain and mud until the middle of June. The average rainfall in this particular place we found out was around 285 inches per year.

We finally licked the swamp by cutting about two miles of canal, some twenty feet wide through it, and tying it in with the sea. Then for all the low lying roads deep ditches were first cut and tied into the canal. By summer we had quite a few miles of roadways built and in good condition.

Air raids were frequent during these early months. Tulagi and Guadalcanal were main targets for Jap planes and we lay between the two. Also Purvis Bay was developed into a large rendezvous for Navy Fighting Craft including Battleships and it became a favorite target. Thus we were situated in the center of a triangle formed by three huge Aerial Targets and so an alert for either one meant an alert for us too. Our PBY's soon became noticed too and came in for their share of bombings. Many nights were punctuated by three of four alerts, making sleep impossible. Old "Washing Machine Charlie" was a frequent visitor. This name was assigned to him due to the odd rhythmic sound made by his plane, making detection easy. His method was to upset morale by making himself a nuisance and keeping us awake more than anything else. He would come in around 2000 hours and stay above the reach of the shore batteries and keep flying around until just before dawn when he would drop his bombs and then disappear until the next night. But eventually we even got used to "Charlie" and did not pay much attention to him.

Three large scale attacks stand out during this period and deserve special mention.

April 7th 1943

Some 125 Jap planes made a concerted assault on Tulagi. At this time we were not very well protected by anti-aircraft and fighter planes were only just beginning to get out to the Pacific area in any quantity. Tulagi and the surrounding area took quite a beating, but the harbor was empty. Guadalcanal sent over all the fighters they had to help out the meager shore defenses. After spectacular dog fighting the enemy planes were finally dispersed and our pilots had downed an average of over five to one. Over half the enemy planes were downed. Tulagi suffered quite heavy damage and casualties.

May 17th 1943

In broad daylight the enemy made a large scale attack on Guadalcanal. Some 150 planes were estimated to be in the attacking force. Landing facilities and shipping at Lunga Point and the Henderson Air Field seemed to be the main targets. By this time the shore defenses were pretty well completed and the shore gunners really put up anti-aircraft shells in a big way. Destroyers and other small navy craft also took a very active part and the fighter force from Henderson Field did a grand job. For the first time we could put up a sizeable fighter force. Over 77 Jap planes were shot down while our losses were only about 15 planes. Most of our downed pilots were rescued. An oil depot on Guadalcanal was set afire, two freighters off shore were sunk, three other Navy Craft were hit, and numerous barges sunk. The freighter Captains attempted to run their ships on reefs after being hit and one succeeded, allowing over half the cargo to be salvaged. The PBY's on our base came in for some of the bombs and two of these craft were badly damaged. This raid got wide publicity and caused a great deal of worry among the home folks. But to us it had become just another raid.

June 5th, l943

On this date the Japs made their greatest effort to break the American hold on the Solomons. Warning came over the loudspeakers early in the afternoon that over 200 planes were heading our way. All hands were ordered to stop work and stand by their fox holes. All equipment was ordered to be dispersed and cleared off the highways. I happened to be inspecting the work of one of the crews working on Water Storage Tanks, located out in the jungle on a hill quite some distance from the camp. Thus we did not get the preliminary warning for we were out of range of the speakers. But we did hear the sirens as they went off on the "Red" condition. We were working on a high hill overlooking Tulagi harbor. We noticed quite a movement of ships out of the Harbor so we figured the alert was quite serious. We stopped work and it was agreed that in an emergency we would get into a large ditch running between the tanks that were being erected. After each one had assured himself of a protected spot, we all sat down to watch the show.

And it was not long in coming, although the planes came in so high that they were mere specks in the sky. But with a roar like thunder all the guns in the area let go and by this time we really had defenses. It was a beautiful clear day with only one cloud in the air and it hovering almost directly over Tulagi. A perfect setup for an air attack. The Jap planes took cover in this cloud and started dive bombing Tulagi and it's shipping. They dropped out of the cloud at a very high altitude and went into their dives. Our planes were handicapped by the cloud formation, it being necessary to catch the enemy as he emerged from the cloud. By this time the earth fairly trembled from the anti-aircraft fire and the little black puffs as the shells exploded were beginning to pock mark the clear blue of the sky.

Seven dive bombers started off the fireworks and the battle was on. One after another they dived towards the ships, dropping out of the sky at a real steep angle, about 60 degrees from the horizontal. The first three were caught by anti-aircraft fire, but not until they had dropped their bombs. The fourth came right through and got a direct hit and apparently got away. The fifth was picked up by a P-38 (Lightning) as he went into his dive and the P-38 followed him down shooting as he came. The Jap plane never came out of the dive but went straight into the water with a big explosions as his unreleased bombs went off, making a huge geyser of water and plane. How the P-38 got through all the flak is a mystery, but he came out of his dive and flew low over the water until he had cleared the island, before he started his climb and then I mean he climbed. Appeared to go almost straight up into the air. The sixth bomber got his bombs away but never made altitude again. He caught fire and after drifting horizontally for a few seconds blew up in the air. The seventh and last bomber came in close on the tail of number six and placed his bombs squarely on the decks of a large tanker at the entrance to the harbor. He immediately pulled up and started to climb. He was plenty fast too, and went out of sight with the shells bursting just in back of the tail of his ship.

Soon the fight settled down in to a huge dog-fight in the air. Some 250 planes were estimated to have been in the original Jap formation. As was the custom, our fighters would intercept them some hundred miles from the target. But this time they had figured us out and were in two separate formations. As our fighters ripped into one, the other went on through to the target. Some 150 planes got over Tulagi. We had about 50 planes to fight them off and they did just that. 117 Jap planes were finally downed and we lost about 30 planes, or a little over half our force. This did not include the casualties of the intercepting group, which we later heard had accounted for every plane in the formation.

It was a thrilling and exciting spectacle to watch, but I would not recommend it to anyone with a weak heart. A couple of times bullets from the dog fighters would spray the territory around us and we would dive for the trench until things quieted down a bit. Most of the dog fighting was done at extremely high altitudes and the planes dove and banked and buzzed around like a swarm of bees. A crippled plane would drop out every now and then and leave a thin trail of smoke as he fell. Others would catch fire and explode in the air. At the same time the shore batteries were putting up a regular umbrella of shells and woe be to any plane that got low enough to get caught in it.

Slowly the battle moved out to sea and things quieted down. Then to take stock of the damage. The Japs really got in their licks too. One big tanker in flames, two destroyers damaged, one sunk, two freighters damaged, one of which sunk. Besides this quite a bit of damage done to shore installations. Many casualties too, especially aboard the ships and on the docks. The burning tanker was a threat for hours after as she had not cleared the harbor. The Captain made a heroic try at saving his ship. He managed to keep his engines going and cleared the harbor. We loaded a barge with fire fighting equipment and sent out a crew to help if possible. But we could not get near enough to be of any use due to the extreme heat. Finally in desperation, the Captain ordered all fuel oil pumped overboard. What a sight. A veritable sea of flames leaping hundreds of feet into the air. We all wondered what would happen to the ship. Then slowly but surely she crawled through the smoke and flames until she was clear. But it was too late. Some of the plates were now red hot, and the Captain just had time to order abandon ship and to jump overboard himself when steaming and hissing and cracking, the hull of the ship suddenly went down by the bow. We helped pick up the oil soaked and terribly burnt survivors and brought them to shore and sent them in to the hospital. Ambulances were waiting for us at the beach.

AIR ATTACKS END

The defeat of the Japs at Tulagi ended the large scale attacks. Not that all air raids ended, we still had occasional ones up until November. But the raids after this were more of the nuisance variety, of only a few planes for observation or photography. None of these caused us much worry or damage. A two plane raid in early November made the biggest impression. One of the planes got a lucky hit and sank a freighter with all of our Thanksgiving turkeys as part of her cargo. Now we really missed those birds, but we made out pretty well at that with canned turkey and chicken meat.

WHAT DOES A C.B. DO?

So much for the combat side of the trip. Now what kind of work did we do and what was my particular part in this work? Our assigned project on Florida Island was the construction of an amphibious repair base for PBY patrol and bomber planes. At its peak it maintained 24 PBY's and 8 smaller fighter craft. All facilities for assembly, maintenance and repair were available. Also the project included a 1000 bed combat hospital to be used for the next pushes (New Georgia and Bougainville). This would be the first stopping place for casualties from these operations. It was also our job to build the camps for the air group, hospital group, and for ourselves.

My main assignment was to take charge of the construction and maintenance of the water supply system for the Base. This consisted of supply pumps, storage tanks, purification and chlorinating plants, and all water mains and distributing pipe lines. Our camp alone consumed some 70,000 Gallons of water per day after final completion. We ran a 6" line out to the shore for ship fresh water supply. This line was used to fill a water barge which in turn supplied the ships with fresh water. The construction of this water barge was another one of my assignments.

It consisted of pontoon barge with two 15,000 gallon tanks water pump, and necessary piping mounted thereon. This water barge became a familiar and very much sought after piece of equipment for drinking water for ships was one item that was very scarce.

Another large additional project assigned to me was the construction and maintenance of an aviation Tank Farm, consisting of twelve 1000 barrel steel tanks and connecting piping, with a supply line running to the shore some three quarters of a mile distant and about 800 feet of flexible hose line carried out from the shore to the ships anchorage. There was also a pumping plant on shore to assist in filling the tanks. Besides this a four-inch line was run out to the service station located on the air field and a small boat supply line run to the small boats dock.

|

|

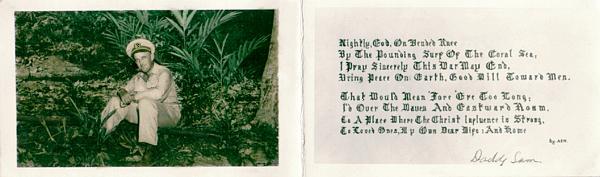

Christmas Card made up by battalion photo lab for Xmas 1943 |

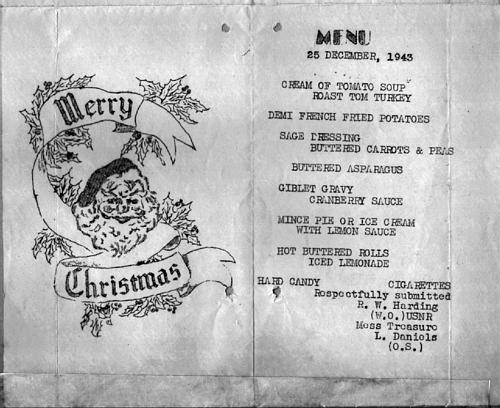

Xmas Menu Dec. 25 1943 |

|

|

|

The C.O.'s birthday cake. Note little bar in rear, also open sides near floor. |

On November 20th l941, I was assigned to Tulagi as Utilities Officer, having charge of maintenance of Water, Power, Communication and refrigeration systems. Here I also acted in the capacity of consulting engineer for the C.O. on a proposed water line for ships supply and Island use. This proved to be one of my most interesting projects. I made a preliminary trip to one of the neighboring islands and located a large waterfall in a section where white men had never before set foot. Taking a good survey party out with me on my next trip, we surveyed a line from the falls to a convenient shore point and then on over to Tulagi proper. A complete report, including map and material requirements was made up and sent in to the island command. This project was eventually approved as far as the boat docks for supplying water for ships and proved to be a real life saver for the smaller ships.

While making this survey we came across some timber that would make good piling. Before the pipe line was completed I was assigned the project of cutting and hauling out a large amount of piling for dock work that the Battalion had under construction. This project turned out to be quite a large scale and difficult undertaking as the timber had to be cut quite a ways inland, and after cutting and stripping the logs had to be hauled by tractors through the swampy jungle to the shore where they were loaded on barges and towed to the sites where dock building was going on.

On Jan. 22, 1944, I left Tulagi having been assigned to the Staff of the 18th Regiment, located on Guadalcanal. Here I was assigned to the O.B. Materials Depot as Yard Officer. All C.B. Materials for the area passed through this Depot and due to a lack of intelligent planning and handling the materials were mixed up and laid out in the mud until they were almost inaccessible.

Yours truly, drilling some of the boys while we are waiting for our ship to come in. (July '44)

Yours truly, drilling some of the boys while we are waiting for our ship to come in. (July '44)

|

And I would have to take over in the midst of the rainy season. My job was to take inventory, clear out those materials that did not belong in the yard. Also have all good equipment, that would not be required for Island Maintenance, hauled out, marked and loaded on to ships for transfer to the new forward area Depot on New Georgia. All the balance of the materials were to be marked and properly stored for local use. This necessitated draining the yard building roads, etc. So for some six weeks I worked a twenty hour day, sometimes 24 hours, and plowed through mud and rain until sometimes I did not know whether I could make another day or not. But in the end I succeeded and got order out of chaos and received the commendation, not only of my own C.O. but of the base Captain too.

A little later when my C.O. had moved over to Gaudalcanal and taken over the duties of Public Works Officer and the Regimental Staff had moved on up the line, I was assigned the duties of Transportation officer for Public Works. After all the kinks had been ironed out of the Public Works and things were operating smoothly, my C.O. decided that I was needed in the Battalion again to take over some work projects, so I was assigned back to the Battalion as Construction Officer and worked on various projects such as storage buildings, Red Cross Canteen, a Recreation Hall and a new dock at Kukum Beach. This kept me pleasantly busy until the latter part of August.

Then one day we were told to close out all of our work and to dispose of all our equipment and get ourselves ready to embark for good old "Uncle Sugar". Now was that one thrilling announcement. For over twenty one months we had been fighting, mud, jungle and disease without let up. Most Battalions had had a rest period between assignments, but we were continually on the job.

So until the middle of September we did practically nothing but wait for that ship to come in. My, but it seemed a long wait too, but finally word came for us to pack and be ready to move out early the next day. And early the next day you can just bet we were all ready. Our baggage started moving out and by evening of that same day we were all aboard and the ship was slowly getting under way. It was crowded and the ship was an old one and dirty and about worn out. But who cared, for we were at least going in the right direction, TOWARDS HOME.

In October of 1944, we landed quietly in San Francisco and turned over a new page and wrote finis to a never to be forgotten chapter of our lives.

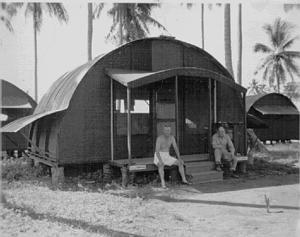

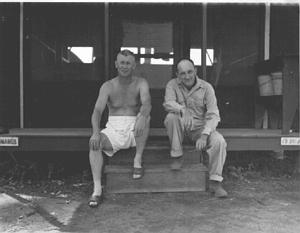

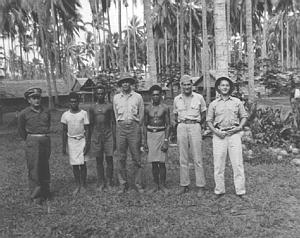

Ch. W.O. Myers, Ch. W.O. Sam Hall - "Two Pals" |

Com. of Coast Guard visits merchant ship

Com. of Coast Guard visits merchant ship

|

Coast Guard publicity group visits British Compound on Gaudalcanal. Note Native Marine Sgt.

Coast Guard publicity group visits British Compound on Gaudalcanal. Note Native Marine Sgt.

|

|

Officers of the 34th Batt. Guadalcanal - 1944

Officers of the 34th Batt. Guadalcanal - 1944

|

Co. "C" - 34th C.B. - Guadalcanal - 1944

Co. "C" - 34th C.B. - Guadalcanal - 1944

|

|

|