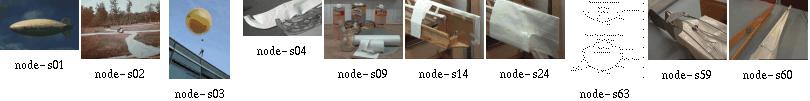

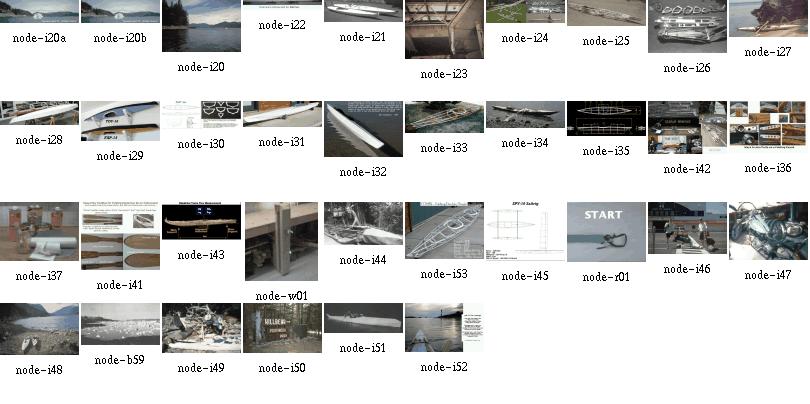

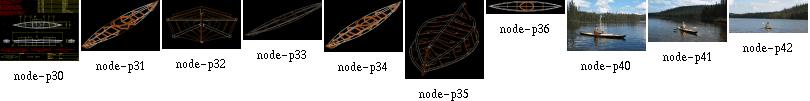

Aircraft Transportation: how to paddle an aircraft... This picture belongs to the Northwest Territories' Photo Database. They have 82 inuit kayak photos, which you can find by entering 'kayak' as the search item.

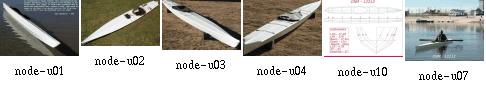

George Dyson´s ''Mount Fairweather'' baidarka was launched in June 1975 at Vancouver City and some days later made its way up to northeast Vancouver Island. The summer solstice of 1995, nearly exactly 20 years later, my brother Gerald and I enjoyed a trip to the Discovery Islands. This trip also was a test of my brother's newly built folding Greenland Eskimo Kayak.

We crossed paths with George Dyson's and similar expeditions. In part, that trip was a sort of a ''dream-come-true''; inspired by our reading and re-reading of George's and Kenneth Brower's books.

Compare the characteristics of our kayaks and let me point out these inspiring journeys, so much more than what we have achieved:

Take care.

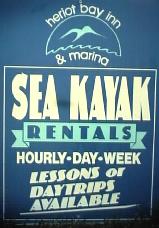

We reached the starting point after riding the ''Victoria Clipper'' from Seattle; there is a bus to Campbell River via Nanaimo. We took several taxis and the Quadra Island Ferry; but the afternoon ''Clipper'' from Vancouver was too late for the Quadra ferry. If you take one of the morning sailings, you get to Heriot Bay within one day. At Campbell River, the local ''Tonys Taxi'' moved us around on Quadra Island. You can rent a kayak at Heriot Bay; so our effort of boatbuilding saved us 180 dollars for a rental kayak:

We move easily, unafraid of what lies below because we ourselves have created above. Our craft forged by our hands, dreamed into existence by our hearts.

This is why we are here. This is who we are.

This wildness. This earth.

These hands. This heart.

This life.

My life.

Unfolding across the infinite span of creation and experience.

Earth, hands and heart pulsating in unison."

Contributed by Ken Lalonde

Edmonton; Alberta, Canada

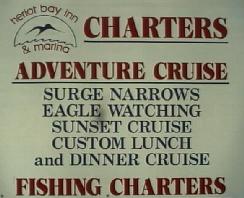

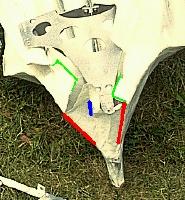

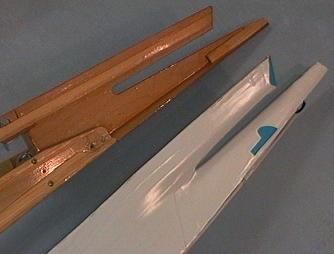

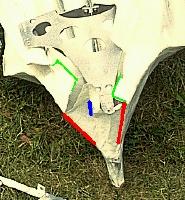

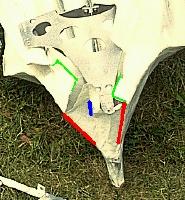

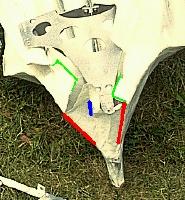

Barnackles and rocks are no problem for these boats. More likely the Surge Narrows, through which we will pass. Maximum current 9 knots. Compare the really large rudder with the small one of my new design, which is still more efficient because the new boat handles a lot better.

We came at the time of maximum currents at the narrows. From someone at Campbell, we learned that in our trip's area were currents of ''40 knots, and whirlpools to the ground''. Although that surely is an exaggeration, we had a lengthy discussion before we entered Surge Narrows; we sat on the small Welsford Island and began interpreting every written word...

The area around Maurelle Island is described in John Ince's well known book ''Sea Kayaking Canada's West Coast''; but since then, the shop at the Surge Narrows Community seems to have been closed a long time. We had sort of a surprise, the day we wanted to take up provisions there. The surprise consisted of a long paddle without breakfast. In contrast to that, the village at Heriot Bay has precise charts, food, camping and everything. Another notable change might be the forest. I don't know how it looked in those times; but today there is a lot of second-growth forest. It is in a good shape, so we realized the fact only after a while. But this resulted in a reduced population of animals. Except of a lot of ravens, we were a bit lonely in those places. We even did not see any raccoons.

In fact, this day started as a perfect day for

fishing, like many other days.

Here, we are landing in search for a camp site. To learn more about our camping, click here.

Realize that the water is already on the move. We didn't and had a somewhat interesting experience right after the narrowest part. It was like someone lift the stop of a huge bathtub...

Here's a map:

And here a flight simulator view from above:

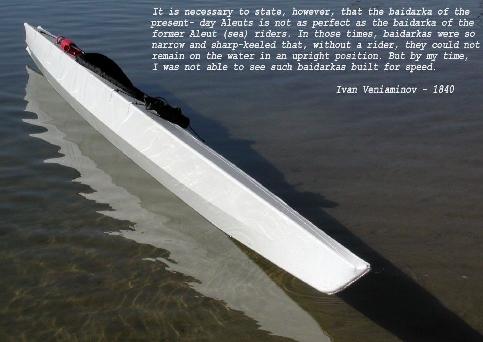

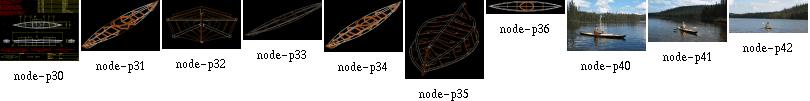

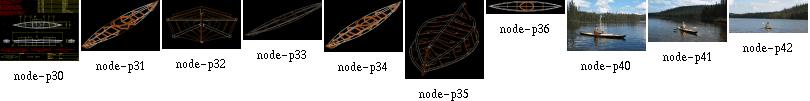

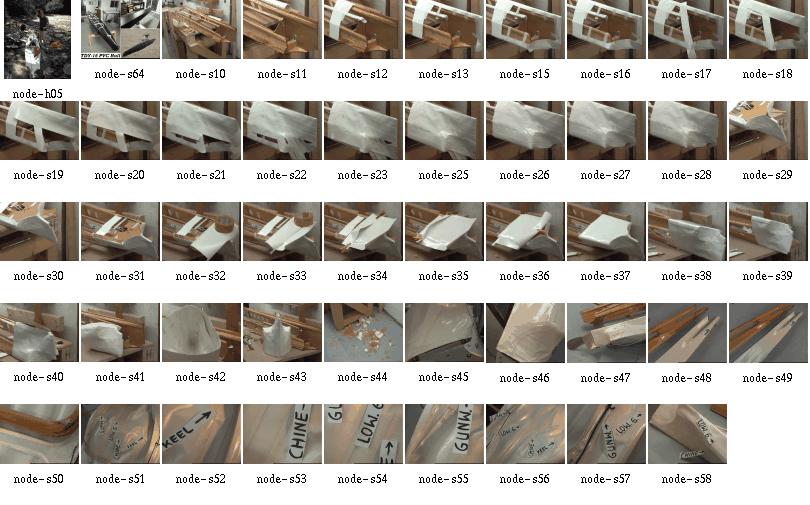

This slide show is about baidarkas. But with a bias towards folding boats and Greenland style kayaks. ''Baidarka'' is a russian word for ''small boat'' which got used not only for Aleut kayaks but especially for Kodiak kayaks which differ noticeably in construction.

This project was initiated by George Dyson's book ''Baidarka''. I consider George Dyson´s three-man kodiak baidarkas to be his most inspiring work, together with the part of the book that treats their history.

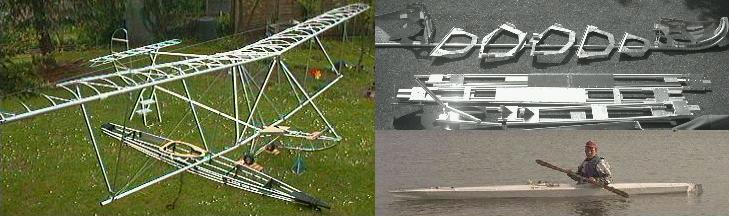

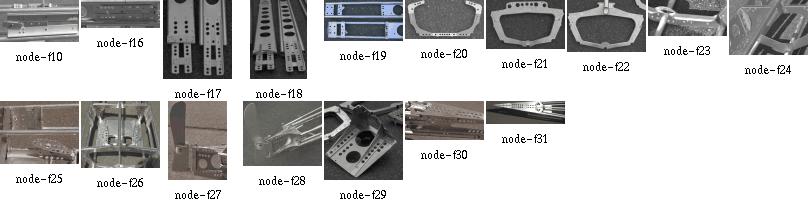

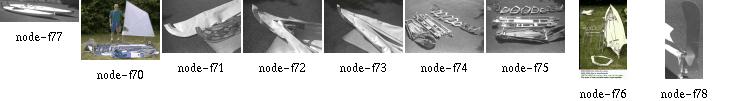

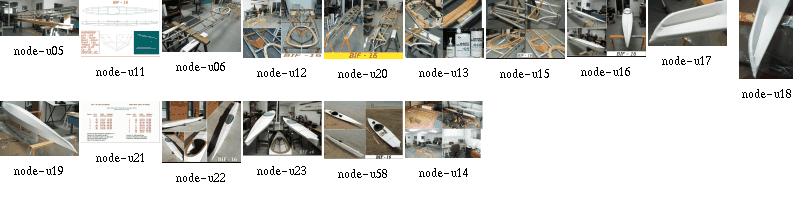

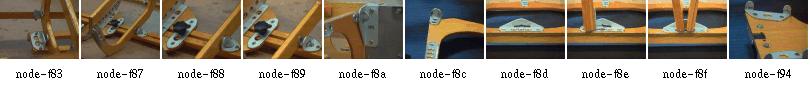

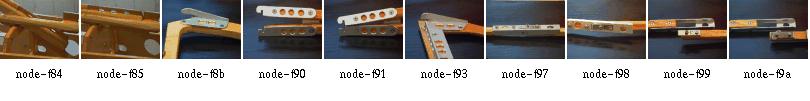

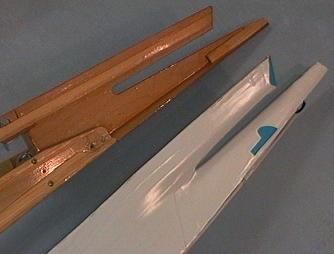

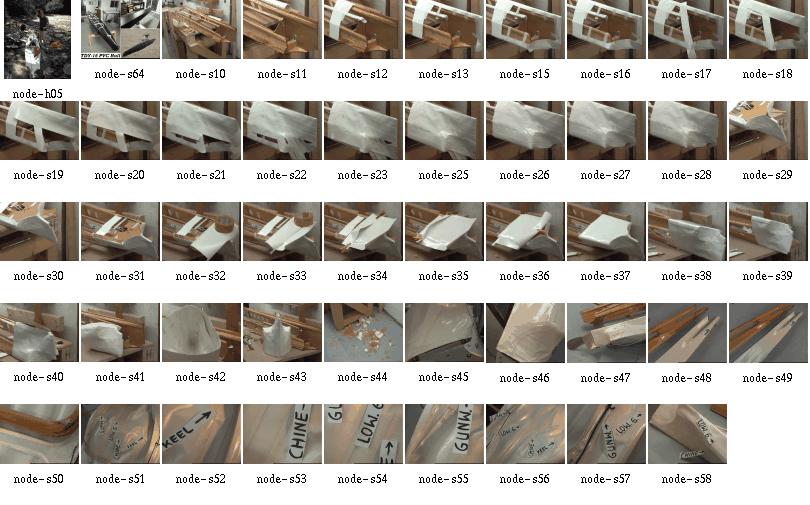

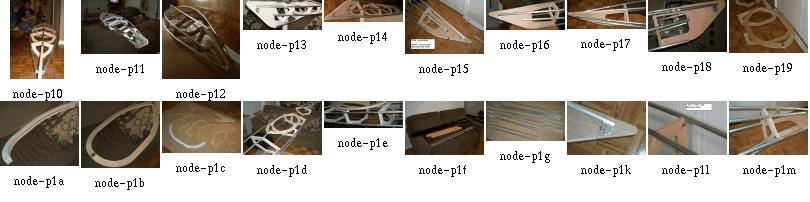

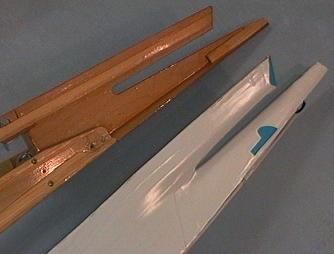

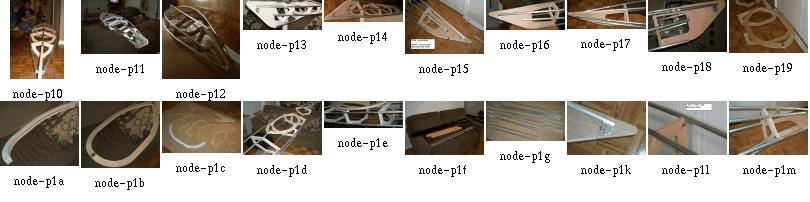

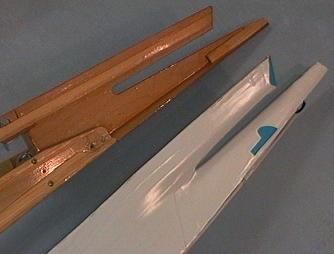

But what got me started into the Baidarka thing in the first place, is the nice connection he made between Boeing aircraft, aluminum tubing, scrap yards and modern Baidarkas. That's why I chose the pic with the airframe and baidarka for this page; my interpretation of the theme has always an aircraft bias towards it. If I cannot build an aircraft due to the huge amount of time, money and experience necessary, the next best thing to build is a Baidarka. I took up the construction of five baidarkas as a means of gaining experience for making an aircraft. Especially the three folders helped in learning to take matters more seriously. It seems that others share the same motivation, for an example take a look here, Or take a look at Geralds kayak parts, although maybe not intentionally, they somewhat look like airplane parts as well. My own construcion in comparison somewhat looks like a tank or gun (better than the furniture I made, it all looks like coffins), and the construction was nearly as much effort as a assembling a small airplane kit.

Also, with a folding kayak, I was depending upon airlines a few times for transportation. This is a good place to return the favor I received from the friendly folks there.

These pages also contain travel pics, shown from the perspective of someone carrying around 120 to 140 pounds of gear per person...

Interested?

Here is more about my BUG2 (acutally named BUG2-2).

Skin-on-frame airplanes...

Spars were 2in aluminum tubing with 0.024in wall thickness, reduced by chemical milling to 0.016in for the outer wing. Talk about optimization...

There is more info on Paul Mc Cready's web site.

Cited from Paul's web site:

It demonstrates what

can be done with low power, when new concepts of efficiency are unleashed

by challenges not burdened by constraints from narrow rules or the need

for commercial production.

We move easily, unafraid of what lies below because we ourselves have created above. Our craft forged by our hands, dreamed into existence by our hearts.

This is why we are here. This is who we are.

This wildness. This earth.

These hands. This heart.

This life.

My life.

Unfolding across the infinite span of creation and experience.

Earth, hands and heart pulsating in unison.

Contributed by Ken Lalonde

Edmonton; Alberta, Canada

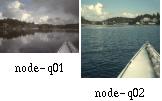

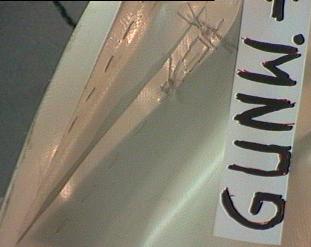

People often ask me that question, and I still have nothing useful to throw at them as a one-shot answer. Especially because it only makes a lot of work. But that bow is an important part of the picture I had in the very first place after reading George Dyson's book: I saw myself sailing an aluminum Baidarka along some part of the Inside Passage. What kept me going full power through all these years was that picture. Then a lot of help from my brother Gerald made it come true; he also took the right photo at the right time, and now it occupies some 2x3 foot on my workshop wall...

Skin-on-frame airplanes...

But what started me into the whole paddling business was this Oregon Coast trip in 1992.

This slide show is about Baidarkas. But with a bias towards folding boats and Greenland style kayaks. ''Baidarka'' is a russian word for ''small boat'' which got used not only for Aleut kayaks but especially for Kodiak kayaks which differ noticeably in construction.

This project was initiated by George Dyson's book ''Baidarka''. I consider George Dyson´s three-man kodiak Baidarkas to be his most inspiring work, together with the part of the book that treats their history.

But what got me started into the Baidarka thing in the first place, is the nice connection he made between Boeing aircraft, aluminum tubing, scrap yards and modern Baidarkas. That's why I chose the pic with the airframe and Baidarka for this page; my interpretation of the theme has always an aircraft bias towards it. If I cannot build an aircraft due to the huge amount of time, money and experience necessary, the next best thing to build is a Baidarka. I took up the construction of five Baidarkas as a means of gaining experience for making an aircraft. Especially the three folders helped in learning to take matters more seriously.

It seems that others share the same motivation, for an example take a look here, Or take a look at Geralds kayak parts, although maybe not intentionally, they somewhat look like airplane parts as well. My own construcion in comparison somewhat looks like a tank or gun (better than the furniture I made, it all looks like coffins), and the construction was nearly as much effort as a assembling a small airplane kit.

Also, with a folding kayak, I was depending upon airlines a few times for transportation. This is a good place to return the favor I received from the friendly folks there.

These pages also contain travel pics, shown from the perspective of someone carrying around 120 to 140 pounds of gear per person...

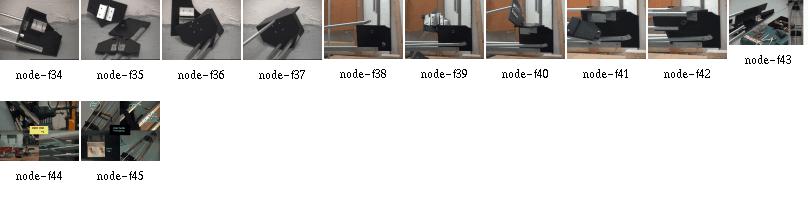

When you take it apart does it become a kit?

Well, yes. My first designs took several hours to assemble. Now I am somewhere at under an hour assembly time. But basically, my folding Greenland Baidarka still is somewhat of a construction kit.

But that is no real problem. My own design assembles a lot better than the two-place folder I have bought. Joints are a lot more precise and rigid, and the overall stability of my frame is worlds apart from that of the commercial product. So it definitely is worth the extra effort at assembling the Baidarka. At least, there is no commercially available folding Baidarka, and I think I know why. I designed my foldables against the structural strength of a rigid Baidarka. Problem is, I only have had two rigid aluminum designs of my own deviation from George Dyson's. This deviation makes it difficult to give absolute numbers.

Here is more on frame stiffness measurements.

Now that I have made a wooden foldable Baidarka, I can tell that my very first aluminum designs were a lot less flexible than this wooden version. This was due to my usage of tubing with very large outside diameter (20mm). Using 18mm tubing should give better results. Using thin-walled tubing will have the problem associated with it that during transport the tubes will get bent and dented.

Anyway. The Aleuts fixed their gunwales into the stem and stern deadwood and made sure they would not move within these joints. Gerald and I simply kept to this rule and made sure that all the foldable longitudinals are thoroughly interlocked to prevent them from changing their length, no matter how thick or thin they are. This was a major design problem for us since anything that interlocks is an attraction spot for salt water. This tends to transform a folder into a partly rigid boat that defends itself from being disassembled (as mentioned in Gerald's "bloody fingers" mail).

And don't forget the skin. A good part of the stiffness of the boat is due to the tension of the skin - it limits the motion of loosely assembled parts.

In this my first folding design, a very loosely fitting skin was laced over a very loose frame. One could forget about the skin's contribution to frame stability; in my case, this worked only in theory. Maybe this is due to actually very small loads, I don't know. Here are measurements that seem to point in the same direction.

However, some parts of that frame were put loosely together for my inability to do a better design. Some parts even had some sort of interlock that I had to cut away to be able to assemble the boat. In essence, being outdoors gave nature a great chance to get me streamlining my assembly procedure.

But it was amazing what loads and abuse that frame was able to bear. This surely is good news for any newcomer. At least in my case even that first design was well good enough to do the job.

Some of the slides are large animated GIF movies. To reduce load time I have cut the assembly process into parts. Just keep in mind that the assembly happens within the skin, but is shown without the skin for clearance.

This whole shebang is available on a CDROM, including several other web sites. It is made by Charles Hall and distributed for production cost.

The animated assembly movies of LostSoul:

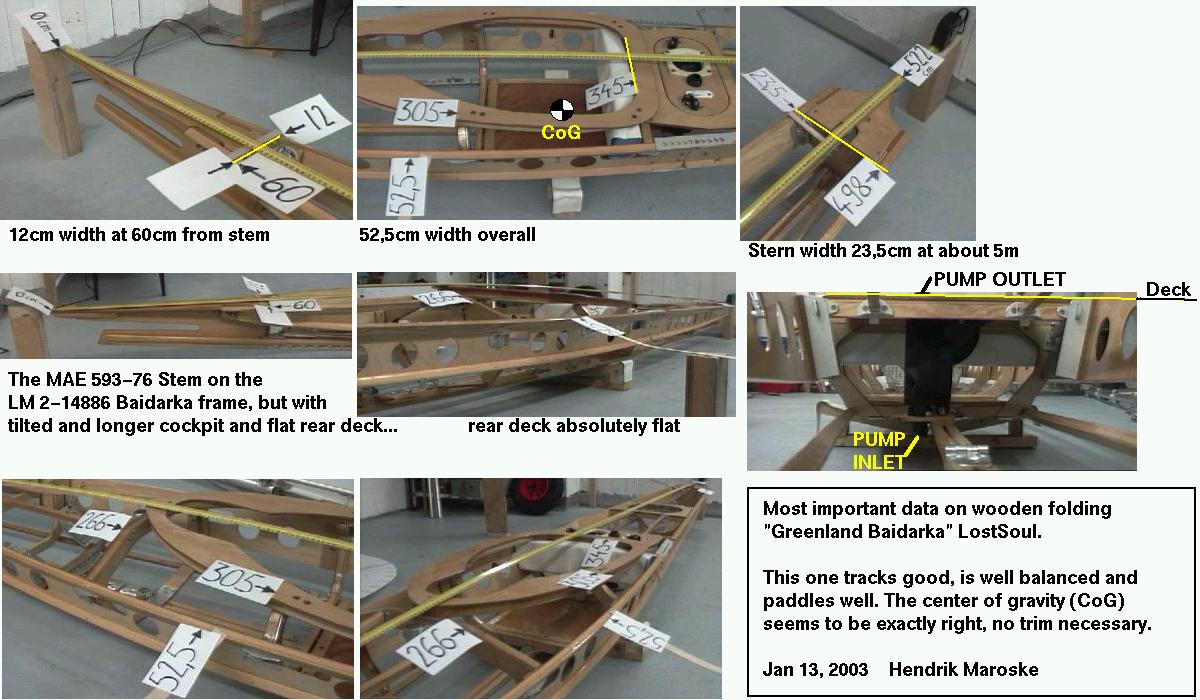

With this design I wanted to reduce the height of the deck stringers. I always wondered if the one-hatch Baidarka deck design really is the big thing, partly because I am making foldable Baidarkas:

Surely the Aleut people had their ways to cope with that, but I was struggling to make my craft seaworthy. According to today's accepted safety standards. I had to change it in order to get a foldable design, and the result is very similar to the Greenlanders, especially since the waterlines of my folding kayaks come close anyway.

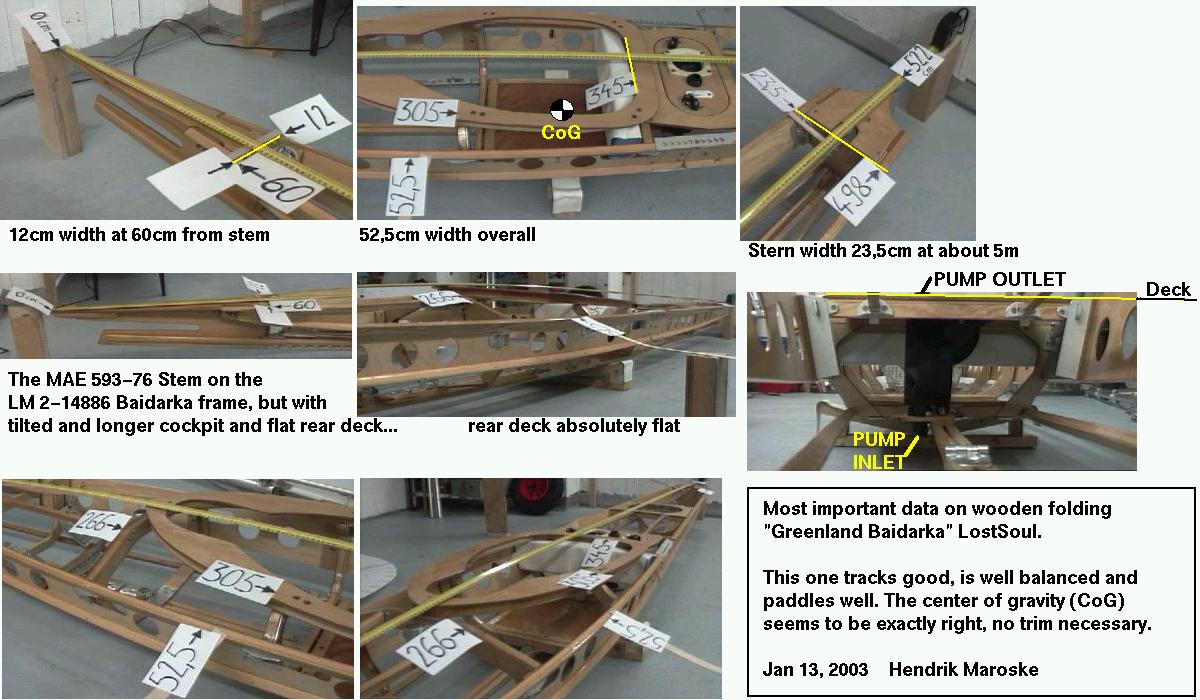

Well, this looks like something. I made a good rear hatch, with the pump installed and everything, skipped that rear deck stringer and now have a nicely fitting tilted cockpit. Seems like progress.

Here is what others have said about my modifications to the Aleut design.

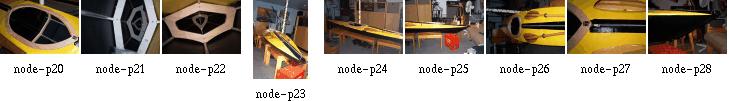

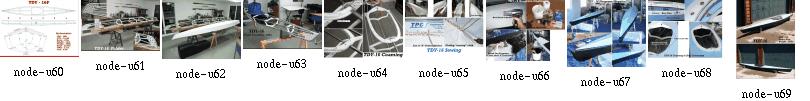

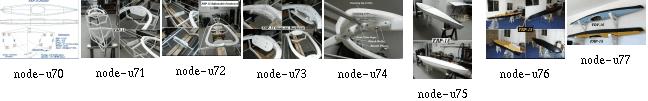

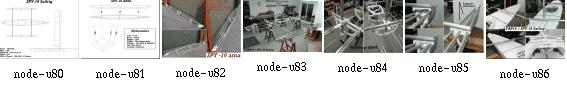

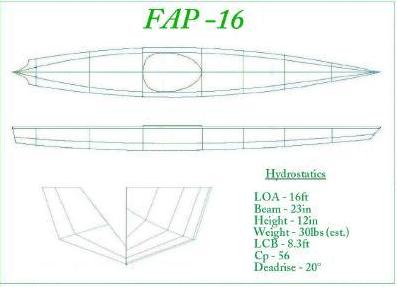

In order to save weight, TDY-16 is built using 3/4in X 0.035 tubing. In addition, there are 6 HDPE cross sections (FAP-16 has seven). The HDPE stem/stern use lightening holes, and the coaming will be light weight fiberglass. The frame, without coaming, weighs 13.5lbs. Completed weight with 13oz. PVC skin material should be approx. 25 lbs.

LOA - 16ft.

Beam - 23in.

Weight - 25 lbs.

Stringers - Aluminum 3/4in. X .035 Walls

Skin - PVC

This Non-Aleut design is intended as a lightweight medium volume touring kayak. As compared to FAP-16, it features a peaked deck to improve interior room for the paddler as well as more storage space. It utilizes thinner walled tubing (3/4" X .035) and six cross sections ( FAP-16 has seven) to reduce weight. The cross sections, coaming, and footbrace are made from HDPE. Finished weight is approx. 26 lbs.

The skin is a sewn, one-piece Polyester (9 oz.) design, and is coated with Neoprene/Hypalon. The hull is covered with eight coats of neoprene, while the deck is covered with five coats neoprene and three coats Hypalon. Neoprene is a bit easier to apply than Hypalon. It cures quicker, and is more durable. Hypalon has the advantage of being easier to fold, and is available in many different colors.

The following pages highlight only those construction details not included with, or that differ from FAP-16:

Stem, Stern and Frame

FAP-16 and TDY-16 Frames

TDY-16 Frame

Coaming Details

The HDPE coaming is comprised of 1/4" baseplate, 1/2" coaming, and 1/8" coaming lip.

Machine screws are used to provide a secure coaming attachment.

Polyester Skin (9oz.)

The one-piece Polyester skin is sewn with nylon squidding line.

The deckridge and stem/stern are cut (seared)

with a propane cutting blade prior to sewing. This process

assures a hard edge that will not separate.

The deckridge will be cut open for the installation of lacing or zippers.

Neoprene

The frame is first waxed to insure that neoprene will

not soak through and stick to either the aluminum or HDPE.

Before coating , a heat gun is used to remove wrinkles

still remaining in the skin after sewing.

The first two coats of Neoprene are thinned with 10percent

Zylene to insure that the neoprene will soak deeply

into the polyester cloth. Subsequent coats are thinned

but to a lesser degree.

Neoprene is applied with a 3 or 4 inch brush. Use short brush strokes and be sure not to brush the neoprene once it starts to glaze over. That will cause ripples in the surface. Maintain a wet edge and move quickly along the surface. Subsequent coats of neoprene can be applied every 30 minutes or so.

When the skin is removed, the inside hull will receive 2 additional neoprene coats. This is not necessary, but will insure complete saturation, and makes for a better looking job.

Always wear a respirator, and work in a VERY well ventilated area.

Hypalon

After applying neoprene, the deck or hull can be coated with

additional Hypalon to give it a color other than black.

Hypalon cures slower than neoprene and requires a longer

wait between coats. Hypalon stays slightly tacky

for a few weeks. Adding Lacing, zippers, flaps, and deck

rigging can be done in a week or so after coating.

Wait several weeks after coating before removing the skin.

I normally wait a couple of months before folding the skin.

The main advantage of the Polyester/Neoprene/Hypalon skins are their one-piece construction and ease of repair. An additional coat of Neoprene/Hypalon every couple of years will keep it looking like new.

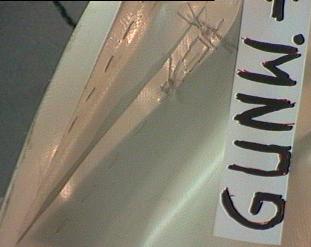

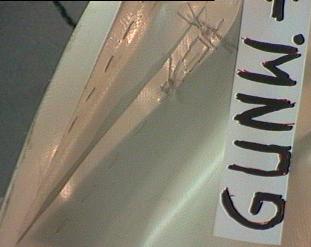

Rub strips can be glued to the keel and chines for added durability.

Skin/Coaming Attachment

On FAP-16, the skin to coaming attachment is accomplished

by wrapping the skin under the baseplate and using snap connectors

(see here for the idea).

On TDY-16, the skin is attached directly under the coaming with machine screws and recessed snap connectors. This is a cleaner installation, but the other method is easier.

Finish

At this stage, all that is left is to install lacing or

zippers, attach the flap, and deck rigging.

The seat is a gunwale mounted sling type similar to that

in FAP-16. A paddling report will be added later.

The cross sections, backrest and footbrace are made of HDPE. The skin is a sewn, one-piece Polyester design. Coating are Neoprene/Hypalon.

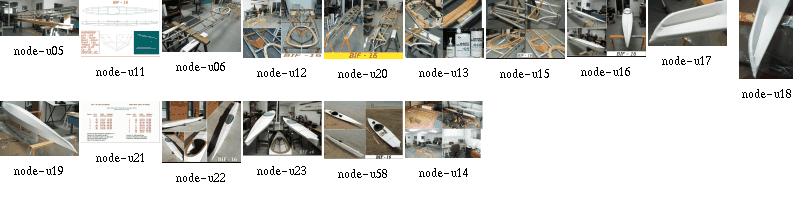

The deckridge is considerably taller than FAP-16 to provide greater room for comfort and storage. Personally, I prefer lower, flatter decks, but wanted to provide an alternative for other builders. This Aleut based frame is made of 5/8" tubing. Though flexible, it showed no signs of deflection in the water. The HDPE cross sections allow for ease of construction and assembly. The tubing size and number of cross sections are the same as the Feathercraft Kahuna (14'6" LOA). Tubing size can be changed to 3/4" if desired during construction.

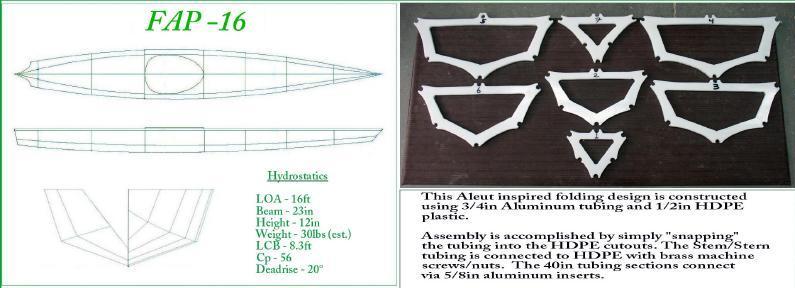

The design goals for FAP-16 were to make the kayak easy to build (Under 100 hrs.), Easy to Assemble (Under 30 Min.), and light weight (under 40lbs). Above all, Tom wanted this boat to perform as well as any non folding skin kayak.

LOA - 15ft. 8in.

Beam - 23in.

Weight - 35 lbs.

Stringers - Aluminum 3/4in. X .049 Walls

Skin - Polyester/Hypalon

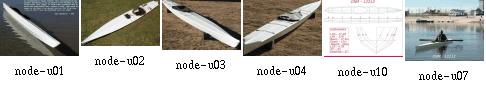

LOA - 16ft 2in.

Beam - 20.5

Weight - 25lbs.

Construction Time - 75hrs.

Tom writes:

I've just recently completed a new kayak after a few years inactivity. The design is a hard-chine Iqyax (CNM-12212) that I built based on a simplified version of George Dyson's method utilizing aluminum stringers with plywood cross-sections. The skin is 8oz nylon coated with several coats of neoprene/hypalon.

Length - 17.5 ft

Width - 17.5 in

Weight - 28 lbs.

Cp - .61

Tom has built approximately 16 boats since 1975, with the first eight being woodstrip/fiberglass sea kayaks. Of that group, two have been Aleut designs constructed from David Zimmerly's offsets in his book "QAJAQ". He built them to scale but made changes to the deck shape. In addition, Tom built a woodstrip version of George Dysons double .

Having grown a bit tired of building woodstrips, he decided to try a hand at non folding skin boats. He first made three George Dyson singles, the first two of all wood construction, and the third using wood cross sections with aluminum stringers.

He immediately realized that these were more seaworthy than were the woodstrip hulls. The flex in the skin and the concave skin shape between stringers, really slowed down the roll rate as well as allowing the hull to conform to the waves.

The first folder that Tom has made, about 1993 or 94, is a folding wooden (pine) version of a Dyson single. Skin is Nylon/Neoprene/Hypalon. Time to assemble - Forever !

His second folder was an

Aluminum/Wood Dyson Double (1996).

Third was an Aluminum/Wood single (1997).

Fourth was an Aluminum/HDPE single- FAP-16(2002)

Fifth is an Aluminum/HDPE single - TDY-16(2002).

Sixth is an Aluminum/HDPE single - TDY-15(2002).

Above is a photo of the folding single that Tom was building 1998(?). You will notice a striking similarity to the "Feathercraft" designs. Since he paddles a Feathercraft K-Light, the similarity is no accident. You will also notice that there are very few parts. This boat follows the KISS principal. ( Keep It Simple Stupid)!

The tubing is all 3/4 in. Aluminum 6061/T6 thin wall. The tubes are attached to the Cross sections using "L" shaped brackets pop riveted to the tubes. The frame weighs about 15 lbs and takes only a few minutes to assemble. The frame has a single stretcher bar at the keel. The skin will be made of 14 oz. pre-shrunk nylon. The material will be coated inside and out with three coats of black Neoprene. The deck will receive additional coats of white hypalon to provide a light color. The boat is 15.5 ft (4.73m) long by 24 in. (61cm) wide.

Tom plans to use zippers along the deck ridge for closure and sewn in sponsons to assure a tight fit and to provide additional stability.

At least in my case, the zipper/sponsons solution has worked more than once. Just take care.

They keep getting lighter, easier to build, and quicker to assemble.

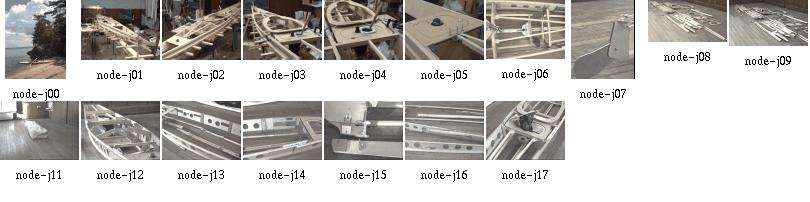

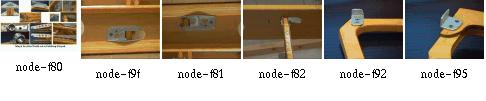

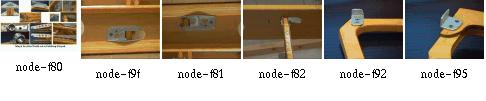

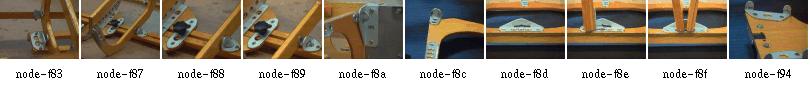

The frame contains four sections which are joined by metal joints.

Total length of the kayak is 5.35m and width is 52cm. It weighs 20kg.

The fore and aft sections are assembled separately. The two middle frames are inserted after stringers and keel are joined inside the hull.

The frames are made of seven-layered, nine millimeter birch plywood except the two main

frames in the middle, which are doubled to 18mm.

The massive parts are all ash and the gunwales/1st chines

are stiffened by 3mm 6-layered birch

plywood.

The joints are made of aluminium and stainless steel parts and all screws are made of stainless steel. Most nuts used are selflocked. All joints are handmade. The joints for the keel and the joints separating the fore and aft sections are tightened by hexagon screws. All other joints are assembled without tools.

The skin is polyester-reinforced-PVC (truck cover) for the hull and cotton/polyester for the deck. The hull is made of 3 parts each side (~36m to sew) but the deck is one piece. The inside of the deck is sealed with a layer of silicone (used for sealing windows etc.).

Assembling starts with the rear section inserted first. This is done because the cockpit coaming is installed with an angle, which provides a better in and out and this is valid both for paddler and framework. A special tightener is used to pull the keelparts apart and stretch the skin. When the keel is joined, both gunwale-joints are also pulled apart one-by-one and joined. The stringers are now joined easily. The last two frames are inserted starting with frame No.4 (backrest) and then No.3 (kneeframe or masik). When this is done the deck stringers are inserted and the last thing is to attach is the cockpit-coaming (steam-bent out of two parts, lip and ring are both ash of 1cm thickness, for a procedure look at Chris Cunningham's article "Building a greenland kayak" in the 'Seakayaker' magazine).

Assembly time is 35 minutes for me (Gerald).

This is the nicest folding Kayak I have seen so far (Hendrik), the joinery is a dream:

Here is Gerald's original page with more info on his design.

And here are all available pages:

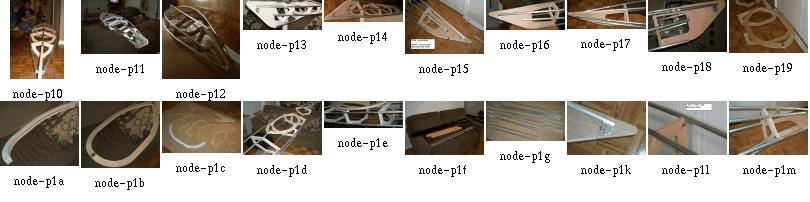

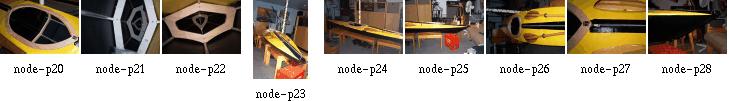

Patrick built his kayak in his living room. He plotted the sections

to scale 1:1 and glued them on 4x4ft baltic birch sheet. That's why

you see white paper on section backs.

Patrick built his kayak in his living room. He plotted the sections

to scale 1:1 and glued them on 4x4ft baltic birch sheet. That's why

you see white paper on section backs.

Patrick has used a small brass hinge to connect the cockpit halves.

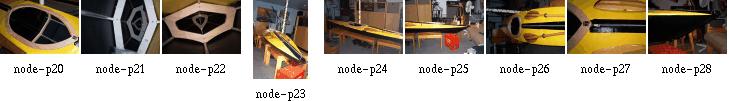

The skin is black and yellow PVC coated polyester mesh 16 OZ, 0.5 mm thick bought

in a truck tarpaulin maker shop. For 100$ CAN he got all needed

fabrics plus a quart of HH-66 vinyl glue.

When Pat has created the DXF the view scale was "1"

so normally when you will print on

a plotter the scale will be ok. But not all plotters

can print that size of paper so to use it

you have to divide in four equal parts and separate

in four different files. Don't forget that little detail.

On vacation in August 2002 Pat went with his friend in their

chalet on the shore of the small lake Dubuc in deep wood on

Mont-Valin a chain of mountain in the north of

Sagnenay river. He is from Jonquiere, a small city of sagnenay

region and brought the kayak with him. First real trial

while fishing rainbow trout and being by mosquito's!

Pat's hull design is made of four parts. Separation approx 1-1/2

feet after stem and stern and one separation in the middle.

He removed all the wrinkles with an iron set to medium

and a cotton shop towel to avoid sticking. This works as well as with a heat gun.

Based upon my own experience, wooden sections are preferable

over aluminum sections because they don't deteriorate

so fast (bending, buckling, denting). HDPE is even more

versatile, but considerably heavier than wood. All in all,

a really good design, especially for the first one you do.

At the left is a pic of a new used hockey bag with all the kayak in it.

Like you see on the pic there is a little measurement error but it is the

perfect bag.

Push and Secure

Pull and Secure

Rotate and Lock

This and That

I keep receiving questions about making PVC skins and thus have re-edited my comments about it into a single file that is a little easier to read. Now you see a mix of four years old comments with very recent ones.

Questions and comments by others are printed in blue.

The images are clickable and lead to the full-size (original) pages.

[ Skin Material ]

[ Welding ]

[ Skinning Sequence ]

[ About Tape on a Final Skin ]

[ About Temporary Skins ]

[ Lacing Skins ]

[ George Dyson's Hypalon Skins ]

[ Thomas Yost's Hypalon Skins ]

[ Epilogue ]

In short, the idea about glueing PVC is to use lots of thinner (Acetone). I had to test the mixture several days and came out with that it is right when the thinned glue begins to run off the brush by itself. Then apply it minimal two times to both surfaces. After letting the glue get nearly dry, combine the two PVC parts and press them well for some minutes.

For the first prototype I sewed two strips of PVC onto a zipper

and glued these zipper strips at the middle of the deck piece. This feature

was as strange as convenient;

it eased assembly and loading of the boat.

For the first prototype I sewed two strips of PVC onto a zipper

and glued these zipper strips at the middle of the deck piece. This feature

was as strange as convenient;

it eased assembly and loading of the boat.

With some grief I dropped this idea and the actual design now has hatches

instead of the zipper. These hatches serve the same purpose except that

it is a lot more difficult to assemble the boat. Also I do not have these

sponsons any more that had to stretch the skin.

Anyway, the www site of STAMOID is http://www.stamoid.com/stamoid or http://www.forbo.com and they have some property sheets about that specific skin material.

The skin comes in doublesided or singlesided PVC covering on a polyester fabric. singlesided weighs 280grams/square meter, doublesided is 430g/m2, tensile strength is better than 1200N over 5cm width.

The singlesided stuff is covered with a dirt protecting finish, which makes glueing and welding impossible and thus has to be removed in the contact area.

Paul Raymond wrote: I stopped at a canvas store today, and he sold me 17 feet of double sided Stamoid for $100, which I think is a good price. Since this is for an aluminum folder, and Hendrik Maroske used it with success, hopefully I will too. I'll find another use for the pack cloth.

Stamoid is what I have used, it comes in both protected and unprotected versions. I suggest to get the thinnest material available, that is, I got the 0.6mm stuff and found it too heavy when glued together, so I talked my supplier into buying 0.5mm stuff for me. There even seems to be 0.4mm material out there, and a way to get material with defects (holes) in it (lots cheaper). This material is so thin compared to my Klepper, how does it hold up on your boats compared to commercial boats? Do you still prefer Stamoid to any other material available?

My most recent Baidarka still is the one from the 1999 Toronto trip. The Baidarka skin was finished late summer 1998 and I must confess I did not use the boat very much since Toronto. I have moved the workshop since, and with it the boat, and since that move the lake is a little more difficult to get to (without car).

Anyway, the pics on this website with several closeups of that particular skin have been made during Christmas holidays January 2002, so you have a guess at how good the skin actually is. It still looks "new enough", is tough as ever and still waterproof. No seams broke.

The skin is nearly four years old, the "unprotected" Stamoid, and ready to go on any trip. I'm satisfied with it. Always cleaned stains before they could wear in (with water only), because without the protection I am afraid to use chemicals to clean the skin.

I see that Tom Yost used polyester material, and then coated with hypalon, which worked well for him, but I wanted to avoid having to use toxic coatings, and the pvc material seemed quicker to skin.

To each one his way looks as the best afterwards. But I would still do it again. It took some time to learn to use a good balance of techniques, stitching, glueing, welding. Basically, my experience with Stamoid and Pattex and Acetone is that if the glue doesn't hold within the first five minutes, it never will. Throw away the pieces that you can and restart. If it holds, it always will. And by "holds" I mean you rip the pieces apart and not the glue fails, but the Stamoid goes apart.

Practice good bonds before doing the skin.

And even more basically the only advice I can give is to really do a few practice runs on the stem and stern pieces with the intention to keep them as samples. This will pay out in the end. Use double sided tape for the first practice run to have a good chance to rearrange things and if you don't want to wait for the glue to settle.

And, talking about abrasion, I cut Stamoid in strips and these were formed with a heat gun to match the curving of the hull before glueing them on over the stringers and where the skin pieces meet.

Generally the heat gun helps a lot to smooth out the results. Afterwards, the warm material is perfectly dry for glueing. It seems that there is some amount of (water or other) thinner in the skin that works against a good bond. Seems to be the stuff that makes the PVC soft.

There's different stuff available for glueing non-rubber zodiacs. 2-Komponent and stays flexible, although quite expensive

Welding is used only in professional applications for truck and tent awnings. I got caught by approximately 3mm material shink per meter as I welded the 5 seams in my hull. Makes funny waves in each section. Took me some time with my heatgun to shrink the whole skin, to take the worst away. :-(

Amateur tools for welding soft PVC without glue, just fabric on fabric, are air guns or the like. Their actual use and temperature operation range seem to fit. Use a rubber wheel on a stick to press the layers together. When it becomes black it's too hot... The professional heatgun that I used only melted the pvc surface without allowing for sticking. Something obviously wrong in my procedure. Welding was Gerald's idea, and for him it worked. My (Hendriks) heat gun did cause some degree of sticking, but not enough to really call this welding. It depends very much on the quality of the skin. If there is anything like "abrasive protection" or "dirt protection" put on it, forget about welding. What becomes black ?? PVC does not seem to change any colour. Is it the glue?? I guess that Gerald was joking. My white PVC just got darker and started fuming. Then it's time to rapidly stop heating. Final question not yet answered: do you stitch only for keeping the pieces together ? In other words, does the skin in its final version rely only on glue lines or is it glued and sewn. I could not really get this out of your description in previous postings.

In my case, stitching was used until the glue bonded permanently. After that time (some 15 minutes), the seams were removed where possible.

All your help is precious: I have just bought wallpaper and a range of water based markers to start the skinning job.

I got the wallpaper trick from Gerald, and it's worth it. You'll easily see how it will be with the PVC, since PVC doesn't have much more stretch than the wallpaper.

One thing about heat gunning:

I never was able to really shrink the skin. It's more like

rearranging it to stress, so that folds and waves remove

themselves. If you would really _stretch_ it with heat,

it will cool off and then be over-stressed and floppy.

So, I used the heat gun only for aesthetic corrections,

not for shrinkage.

Paul Raymond wrote:

Has anyone else had any luck using pack cloth, which comes coated one

side and dyed, and adding additional polyurethane?

Michael Daly wrote:

I have never tried, but wouldn't bother. Coated pack cloth, in addition

to having a urethane coating on one side, has a durable water repellent

coating on the fabric as well. The purpose of the latter is to prevent water

absorbsion into the thread and so enhance its waterproof properties.

I'm willing to bet this coating is what prevents a good bond with the

subsequent polyurethane coatings you apply. You need an uncoated fabric to begin

with, or at least one that has only a "coating-friendly" treatment applied.

Preventing any good bond, exactly. I had oversensitized my right thumb from rubbing the material with Acetone to remove the protection from the glue areas. Definitely NOT the way to go. Although the coating really is good, waterproof and repelling dirt.

Stefano Moretti wrote:

I need much help from more experienced skinners. This will be my first

attempt. I've finished the frame od the foldable with much satisfaction. It is

not wobbly as when I first started.

Congratulations! Now proceed to game level 2 :-)

1) Make hull and sides from one single piece, cutting "V" shaped slots in bow and stern. Seen this picture in FOLBOT virtual company tour.

No way. I also tried this. It is better to do it right, from the start on. Buy a roll of wallpaper and make cutting patterns. Cut the patterns in stripes following the chines, guns and keel.

2) Overlap hull and deck skin over the gunwale chine by more than one inch

Again, its better to go right through it: begin with a large overlap for sewing and then cut it small before glueing. The skin is not easily folded with such thick glue strips.

From my experience, I consider everything too thick that is overlapping more than 3/4 inch or has more than two parts overlapping at the same area

3) cutting deck from mid cockpit to bow, and from mid cockipt to stern, so to reduce the wrinkles and dragging all error towards the cockpit area where the big hole would accomodate much wrinkling. Done this with 3 mm plywood in clc kayaks, should work.

The less glue strips (rsp. easier folding), the better. If you go without deck ridge, there's no need to go with the deck seam. Always proceed to the ends rather than towards the cockpit. Otherwise, you end up having a slack skin at the cockpit.

4) for all unexpected problems and some extra stiffness (still very much debated I know) I would add two small section sponsons just below gunwale.

In my case, both designs worked well. Especially with cold, wet skin, sponsons give you the chance to re-stretch it.

How do you cut and glue around the Aleut stern.

Making these end pieces helps a lot in acquiring the skills to work with PVC. Throw away a piece if you are not satisfied. The next one will come together a lot quicker.

Having made a pair of useful end pieces, the large skin panels are glued over the end pieces, and when all the skin is done I add a nice looking finishing layer over the end pieces, smooting out the curvature and hiding all the seams, glued patches and the rugged connection between skin and end piece.

After having made the skin, I rip out the innermost PVC layer of the end pieces, thereby ensuring that the stem and stern will always slide into them without too much trouble. So, the very first PVC layer for these pieces is attached only very temporarily, with double sided tape or masking tape.

Do your PVC skins have a seperate panel for each Keel to chine, Chine to gunwale, and gunwale to deckridge, or are you able to cover greater areas at once?

Greater areas simplify nothing. They make things more complicated, and if something goes wrong, you'll have to throw away more skin. My boats have fairly high gunwales, more like 'planks'. The sequence is like this ( I began inside-out, here's a sketch, but that is not absolutely necessary):

What weight PVC would you recommend ?

The thinnest/lightest you can get. I have used .6mm thick stuff and next time will definitely use .4mm instead. Because every seam doubles the thickness, and together with the glue it really gets stiff. If you expect trouble somewhere, use the thinnest stuff you can get and apply strips wherever needed. The procedure for the stem/stern I described yields very stiff results.

From now on I assume that you have made a set of good end pieces and are ready to skin. PLEASE, use wallpaper for making cutting templates. Cut strips aligning to chines, guns and keel. (in my case, 6 strips + 1 deck strip). By any means make strips the whole length of the boat. Leave out cockpit rim.

On the inverted hull, sew together the two strips that meet at the keel and go up to the chine stringer.

Sew strips loosely together using 1 inch spacing between seam stitches. Sew only where PVC is cut away anyway. This routine worked best for my Greenland Baidarka with only one chine stringer and the gunwales having an upper and a lower stringer.

I used a twohole punch to make a row of holes at a long side of a large piece of PVC and temporarily sewed it directly onto the frame prior to glueing it to other pieces. This way I could reduce the count of folds in the skin.

Sew the two strips that go from guns to chine to the ones you just sewed together, leaving off the stripe between lower gunwale and chine and thus using large seams over the hole (stitches 5-7cm apart).

Loosely attach the previous mentioned strips to the guns (stapling them on wood frames, using tape on aluminum) and rotate the hull

Sew on the deck strips with a rough seam, stiches some 3cm apart

Use heat gun to remove wrinkles everywhere. Rotate hull.

Use heat gun to stick (weld) the remaining two strips to their place between the lower guns and chine stringer.

Remove the large seams under the two newly attached strips. Use heat gun to partially lift off those strips and reattach them without wrinkles.

Lift one yard of each strip, clean contact area thoroughly, apply "hendrix mixture" and glue them together. Make sure glue line is only 1.5 - 2cm wide. Glueing procedure described later. Work towards the ends of the hull, cleaning and glueing.

Let the glue dry. Cut excess skin at the newly made joints.

Use heat gun to remove wrinkles. Do not generate excessive heat at the glue strips!

Redo the keel seam (the butt type, not overlapping!). Now space the stitches 1cm apart. Cut excess skin. Now the borders of the two skin strips just touch each other.

Use heat gun to remove wrinkles at keel area. Cut keel strip (3cm wide) and lay it over the keel. Use heat gun to smooth it over the keel's curvature.

Remove keel strip, clean keel line, 1.5cm in each side (=3cm wide total).

Remove keel seam for two foot length, glue the keel strip where the seam was, to make it watertight.

Redo gunwale seam. Proceed as with keel.

Glue small horizontal skin strips over the bow and stern to generate the Baidarka's extremities. For Greenland Kayaks, much less work since larger patches usable.

Cut and seal the cockpit area.

Don't forget to make sure there is no "protective impregnation" of some sort over the PVC. Otherwise, you get lots of additional work to clean the glueing areas.

Be meticulous at the cleaning operations.

Always make test specimens and rip them apart to see whether the glue mixture and/or cleaning operation was successful.

Well, "hendrix mixture" goes like this:

- thin the glue until it quickly runs off the brush by itself.

- thoroughly mix

- apply three times, let dry after each application

- contact the parts

My glue is the German "Pattex Transparent", thinned with Acetone. You might want to ask my brother Gerald, who is a chemistry professional, what the american equivalent is.

I put a rub strip over every seam and have had good results.

In my first attempts, I also have put rub strips inside the skin; this is not so good, since skin folds less easy, is more heavy and tends to develop folds. Also I simply cannot glue well on the frame from the inside.

On my first foldable Baidarka, the double sided tape that had to closepart of the deck seam and seal it watertight, became an ugly black smeary, slimy thread after a two-week saltwater session. I'll never do this again...

Now, it seems that most of us just try with the expensive skin (me included), ignoring the possibilities of tape (although I tape virtually everything) and clear plastic. I just always had tried to avoid the additional work involved.

But that can be real fun; here is an account of what can be achieved, if you really want.

Tom writes:

This temporary folding skin is made of PVC to test the

viability of the material as a one piece hull.

In this test, I've pulled the skin fairly tight using

squidding line but am careful not to

over stretch. There are still a few wrinkles in the

skin, but to this point no heat has

been applied. The "Real" skin will be made of higher

quality, thinner, Stamoid PVC.

This is a good picture. I have seen this quite often with my own first PVC skins.

My own experience at working with very large PVC skin panels is that bulges develop at the few remaining seams which show that the skin doesn't fit closely. These bulges were quite sharp since in the other places the skin would fit very smooth. Afterwards it was impossible to remove these bulges.

If you look closely, you will see the vertical folds in between the gunwales and stringers. This is exactly the problem zone, they tend to concentrate right before and after the cockpit. On the other hand, the keel area looks good... how about a single piece for both keel panels? Now, the keel needs a rub strip anyway, so there is also no real advantage in doing it in one piece. Doing it in two pieces yields much smoother stem and stern parts. You will find that narrow PVC panels are much easier to work into a pre defined shape.

My own conclusion is that a one-piece skin is perfect for testing the frame before doing the final skin. This one took less than three hours to make. Very motivating.

Tom writes:

The Stamoid has unidirectional fibers which would only conform

in one direction, so it wouldn't take the shape of the hull

without getting all wrinkled at the stringers. In addition, and

the thing that bothered me the most, was the fact that the Stamoid was easy to tear when I

pulled on the stitching that I used to stretch the skin. This

happened in only one direction , parallel to the fibers.

I've never had a skin material

tear before, so it really caused me concern.

I still feel that a one piece PVC hull is workable, as it has been

done by others. The problem I had was trying to do it with Stamoid.

The black PVC had

multidirectional cloth , the same that I use on my sewn skins, so it had

the ability to conform to the stringers. I didn't have enough of it for

the entire boat so I

purchased Stamoid thinking it was made the same way. It wasn't.

About the Stamoid tearing easily when sewn; that is a good point. If I recall correctly, the thicker 0.6mm variant would not tear as easy as the 0.4mm one. Anyway, I had no other comparison and was satisfied with the 0.6mm stuff. Although I have never seen a skin tear on my boats, even on tar or stone beaches. And back then I simply took it as normal, but shame on me, I have used only a small amount of really thin Stamoid, mostly using the 0.6mm material. I stand corrected in having said the thinner material is better. Maybe the thicker material has a stronger cross weave respectively more cross weave?

Here is what I found today, 28OCT2002 when measuring the tearing resistance with a thin line that I would use for sewing the skin (25kg test Dacron). I punched the "sewing" holes an inch from the border and an inch apart:

Direction crosswise to roll length (in roll axis):

20kg,18kg22kg (average=20kg)

Direction following roll length, that is, the fibers,

if fabric were of unidirectional fibers:

12kg,14kg,20kg (average=15kg)

To me the difference doesn't look so alarming, but yes the Stamoid actually is not at all multi/bi directional.

During my boat building runs I noted a rather large variation in quality even in a single roll. Also, the material sample I just have tested is 0.55mm thick instead of the supposed 0.6mm. The resistance to tearing with a strong line also varied a lot and was kept at bay in using a small distance between stitches. In the end I glued everything anyway. Also I used to use a thinner, weaker 10kg line that would rupture before the skin would tear and would not interfere with glueing.

I never could achieve anything with "lots" of heat shrinking on Stamoid. Only with narrow strips that were formed with the heat gun. Heat only re-aligned the weave within the PVC very lightly.

I also have heard of several people trying a one-piece skin, but my own results were frustrating (see above). See here for Patrick Poirier's results.

I know several people who have used hypalon on folding skins and I haven't heard complaints. Of course, commercial folding kayaks and most inflatable boats also use hypalon coatings, but those are impregnated under pressure and thus bonded more completely. But it is a good sign that the river rafting industry has stuck with hypalon for at least 20 years.

I should have all kinds of free time since I finished my new book, but I still haven't found time to revive the BHS. Fortunately, the skin boat revival has a life of its own, and is doing fine.

There's an excerpt of my new book, with discussion, at:

best wishes,

George B. Dyson

Click here for a

view of a Thomas Yost's design for a folding Hypalon skin.

Click here for a

view of a Thomas Yost's design for a folding Hypalon skin.

Click here for a

view of a very easy method of lacing the skin to the frame.

Click here for a

view of a very easy method of lacing the skin to the frame.

"what's that"

I answered "my boat".

"a boat?"

"yes. It's a Baidarka." Having said that I thought he'll ask something about what a Baidarka is. Especially some question about that bow. Instead came

"why'd you wrap your boat in plastic?"

Click here for

Thomas Yost's design with a folding

hypalon skin.

Click here for

Thomas Yost's design with a folding

hypalon skin.

Click here for a

view of a very easy method of lacing the skin to the frame.

Click here for a

view of a very easy method of lacing the skin to the frame.

Gail Ferris' paddle drawings are barely visible in thumbnails, but worth looking at in fullsize!

Paddle Drawings by Gail Ferris:

Curved Bone Up

Ilulissat 1 bone edge

Ilulissat 2 bone edges

Kitdit Vestejland

Lars Jensen

Nathanial Jensen

Neils Moller

Odense Upv 97

Weathered Upv 97

What you're looking at is just an overview with a few interesting images. Here is more info on all our folding Baidarka designs:

[Design]

[Construction]

[Parts]

[Joints]

[3-D]

[Complete Framework]

[Skin The Frame]

[Stem]

[Stern]

[Rudder]

[Gunwales]

[Frames]

[Stringers]

[Cockpit]

[Materials]

[Pump]

[Sail]

[Paddle]

[This And That]

Well, the basic folding boat design procedure goes like this:

That was actually step one.

That was actually step two.

That was actually step three.

That was actually step four.

Still reading?

We actually have managed to collect a few useful design and construction tips,

and the purpose of the design page is to divert you into the appropriate sections, depending

upon your preference.

Since this is a 'crosswise' entry,

you will have to use the  button to get back to

the design page.

button to get back to

the design page.

Design bits and pieces:

SPY-10 Sailrig by Thomas Yost

Dyson Style Two-Seater Folding Baidarka by Thomas Yost: Seat and Frame

Zippers: Easy Loading

Deck Ties

Skin Quicklace

BIF-16 by Thomas Yost: Perfect Bow

Sliding a Curved Bifid Bow Into The Skin

Oval Aluminum Tubing

Thomas Yost: Bending Tubes

Bending Aircraft Tubes at Mark Smith's Shop

QUESTION: Pin Joint for Stringers

Skin Cutter

The PVC Glue

Kayak Camping: My Sail is My Home (Ready for the Night)

Epoxi

Rudder Pedals After Use

Simple Carrying Toggle

This is my grandpa Martin Seeger with his folding kayak, assembling his own design. He is not exactly a contributor to this page but my thanks go to him anyway. He'd have a lot of fun with this page...

This pic is dated about 1928, for all the folks who think they invented the folding kayak :-)

well, that's it :))) Tonight for the first time I disassembled the Folding Greenland Baidarka from within its skin and was able to get all parts out if it :)

Well, nearly all... I had overseen a tack which permanently fixed the skin to the keel right where the rudder is and where nobody can reach the tack to pull it out! The good part of the story is that I have sewed only partial deck covers. I will not glue the final deck cover onto the skin before the cockpit sock is ready and the equipment bags have been fitted to the hull form and attached to the hatch closures. So, for quite a while, the Baidarka will stay without the final deck cover. This is no problem since I already have cut the piece and can glue it on within an hour or so.

With my aluminum Baidarka, the first disassembly was more of a disaster. I had skinned it over the xmas holidays while my family was out. The Baidarka occupied our whole living room. Two hours before my family returned, I was ready to disassemble. It did not work. A stringer was fixed by the skin and could not be removed without sawing through the aluminum tube... I picked up my wife and kids, and they went in and I brought their luggage up and carried the Baidarka sack down, living room looking a bit untidy. That was a close call...

Anyway, here is how my brother Gerald and I have once assembled our kayaks in the field, entertaining the whole small village for the best part of a whole sunny day:

This sailrig is designed for use with FAP-16. It can be adapted to other folding kayaks with minor modifications. The amas are constructed using aluminum tubing, HDPE Cross sections, and a nylon/neoprene skin.

This ama design is based on, but not a copy of, the Chesapeake Light Craft Eight Footers that appear in Woodenboats #131, July/August, 1996. The CLC amas are made of plywood and feature a "V" shape cross section. The SPY-10 folding ama utilizes aluminum tubing with a nylon/neoprene skin. The cross sections are "Hard-Chine". The amas are 10 feet long to approximate other designs currently in use.

With 3 cross section and 3/4"X.035 tubing, the amas weigh 7lbs. each. Estimated weight with Nylon/Neoprene skin is approx. 10lbs. each. The 120lb. displacement figure is at point of submersion. The twin 10 foot akas are made of 1.5"X.049 tubing and break down into three sections. The center section is 4 feet, and the outer sections are 3 feet each. There are two 27" inserts per aka, which are made of 1-3/8"X.058 tubing. The akas are spaced six feet apart as Tom felt that was a minimum distance for paddle clearance.

Tom's workshop is pushed nearly to it's limit when the sailrig is assembled.

These are boats (and nuts). They fly and ride trains and buses at no extra fee (the boats, not the nuts).

Carrying the kayaks in airplanes, trains, buses and taxis was no problem; all american transportation had facilities to handle bags of that size. Even with the Victoria Clipper, from Seattle to Victoria, this was no problem, although they had all their staff carrying our luggage on board. It might become one, when everyone tries to carry luggage of that size...

What has a motorcycle to do with kayaking? Easy: the taxi driver very kindly drove us around with our large heap of luggage. He is a Harley Davidson expert and might have all the parts you need for your pre-war bike. We had some time left when we were to go to the ferry, and instead of just dropping us off, Tony showed us his workshop.

The Lightest Breeze

The Lightest Breeze Enters My Mind,

And All Before Is Left Behind.

For It Is Not Fate That Brings Me Here,

But Rather A Need, Perhaps A Fear.

The Winds Of Time Have Happened By,

And Left Me With This Clear Blue Sky.

The Ocean Swells Do Comfort Me,

The Waters Glow, My Light To See.

For All That Is Will Always Be

Deep Inside A Part Of Me,

Until My Life Upon This Land

Assumes It's Place Amongst The Sand...

T.Yost

George Dyson's ''Mount Fairweather'' Baidarka was launched in June 1975 at Vancouver City and some days later made its way up to northeast Vancouver Island. The summer solstice of 1995, nearly exactly 20 years later, my brother Gerald and I enjoyed a trip to the Discovery Islands. This trip also was a test of my brother's newly built folding Greenland Eskimo Kayak.

We crossed paths with George Dyson's and similar expeditions. In part, that trip was a sort of a ''dream-come-true''; inspired by our reading and re-reading of George's and Kenneth Brower's books.

Compare the characteristics of our kayaks and let me point out these inspiring journeys, so much more than what we have achieved:

Perfect paddling weather. The way I got there was this: on a Friday noon I was working in England on a piece of software. Already a taxi was waiting to take me to the airport. At the same time, one of my bosses showed up with a commanding voice and a ticket to Toronto. So I repaired that code, got my plane home to Germany that Friday, packed the Baidarka on Saturday and catched the plane to Toronto on Sunday, showing up on the check-in with a previously undeclared bag of 2m times 50cm times 30cm weighing 90 pounds. It was an eventful check-in, but eventually the bag got on board for about 200 US dollars.

Nearly two weeks later, still in Toronto,

I managed to get a long weekend off, but I would only know that

I am off when I already sat in the car, driving north. Whew.

Dear Friend, now this is the end of our story. It started out as a dream and now has become reality for us. That other reality that we have to live in is already waiting for us to return to.

Wondering why it is this way

Spending Time for Naught.

Wasting The Best Hours of the day

Knowing my Soul is Bought.

For Working Here Is Life Passed By.

Freedom Traded For A Clock.

I'd Rather Be Sitting Under a Tree

Staring At a Rock.

Contributed by Thomas Yost.

I hope these pages contain something useful for you; if they get known among some home builders, that's fine. But you can imagine that none of the authors will like to see his pictures spread out and sold without knowledge and permission; so please respect their property. My thanks go to all contributors. Most of the addresses listed below are unfortunately out of service now.

George Dyson, the classic in this field (thank you for the superb fotos)

gaileferris@hotmail.com

gaileferris@hotmail.com

Thomas Yost Littleton, Colorado 80122 (Your pics are the salt in this soup :)

Gerald Maroske (without your ideas this wouldn't have happened)

I also owe more than a "Thank You" to these editors

of books and articles:

John Brand (Little Kayak Books)

H.C. Petersen (Skinboats of Greenland)

John Heath (Articles in SeaKayaker)

Nikos Drakos, head of the "latex2html" team for

their TeX to HTML converter

David Walker for the cool 100percent sticker (greetings

to all Linux users :)

sure the developer of the origami folding text editor without which I'd have a lot of trouble writing these files because my setup is a lot faster than cashware :-)

and last but not least Charles Hall who went through the work of making the robroy server and Baidarka CDROM where this slide show and a lot more can be found.

, thanx Linus!

, thanx Linus!

Those things were built to make a living; not just for sports.

For a description of baidarka designs, click here.

Image size: 1359x527 pixels.

Curved shaft whitewashed old paddle with bone tips found in the loft over the church

Measured and drawn by Gail Ferris. Dec 4th, 1997.

Gail E. Ferris

Image size: 1681x677 pixels.

Paddle with single bone edge at Knud Rasmussen Museum, Ilulissat

measured and drawn by Gail Ferris 6/23/95

Gail E. Ferris

October 18, 1998

Image size: 1811x751 pixels.

Paddle with two piece bone edge at the Knud Rasmussen Museum, Ilulissad

displayed on the third floor. Measred and drawn by Gail Ferris 6/23/95.

Image size: 1997x661 pixels.

Kitdit or Vester Ejland paddle at the Aasiaat Museum

Measured and drawn by Gail Ferris 06/22/95

Image size: 1673x617 pixels.

Lars Jensen, son of Nikolaj Jensen, Kullorsuaq Greenland kayak paddle specifically

designed without a rib down the center

Measured and drawn by Gail Ferris 9/95

Image size: 1436x636 pixels.

Nathaniel Jensen paddle designed with a ridge down the center to split the

vortices by Nikolaj Jensen, Kullorsuaq, Greenland

The shape of the blade cross section at 2cm is a long rectangle with rounded edges.

At 20cm the cross section is an ellipse without any rib down the center.

At 25cm the rib on the face of the paddle blade starts to form and at 40cm

the rib becomes highly defined.

The loom begins at 76-77cm where there is a step down.

length overall: 217cm

length of loom: 61cm, rectangular

blade length: 77cm

Measured and drawn by Gail Ferris 9/95.

Gail E. Ferris

Image size: 2317x777 pixels.

New paddle made by Neils Møller at the Upernavik Museum

A thin blade with a shallow taper

This new paddle was very smooth of light yellow fine grained wood, without bone ornamentation and an elliptical cross section.

Similar paddle on Rosa Thorliefssen's father's kayak in Innarsuit which also was very likely the standard paddle in the 1930's (very light and especially long).

Length: 226cm

measured and drawn by Gail Ferris 6/29/95.

Gail E. Ferris

Image size: 1849x705 pixels.

Kayak paddle collected in 1890's given to Upernavik Museum from Odense Byter Museums appears to be

very similar to a paddle Gail Ferris measured June 1995 from Kiidlit/Vestejland, an Island

on the western edge of Disko Bay.

This paddle has a very distinct ridge down the middle of the blade which the paddle from Kiidlit did not have.

This is a very thick paddle.

Overall length: 200cm

Bone edge is 1cm wideby 39cm long by 0.75cm thick.

Bone tip is 8cm long

ransition from paddle blade to the shaft starts at 75cm from the tip.

You asked me why the diamond shape in Nathanial Jensens paddle affects the wake vortex configuration by splitting them. Well Nikolaj Jensen and I both agreed that the annoying thing about a flat faced paddle is that the paddle chatters or wavers up and down in the water during heavy acceleration. And so to eliminate this is to make the paddle blade face diamond shaped.

I think the best way to discribe the effect of a diamond shaped paddle blade face is that it causes wake separation sufficient during start-up acceleration to eliminate the combining of the wake from the power face and back face from generating perceptible wake drag. The wake generated on the power face is divided into two simultaneous wakes one on the top and one on the bottom of the face instead of one alternately coming off the top and then again off the bottom.

Also I think if you look closely at the unusual shape of both the Odense and most particularly the Kitdit paddle you will see that there is a highly exaggerated roundness at the 40 and 60 cm. sections where the wood junctions with the bone edge of the paddle forming a concave area at the juncture of the bone with the wood. I noticed this very extreme juncture area and wondered why it was so rounded up rather than delicately flattened to a nice gentle integrated line with the bone and wood melling together with no concavity rather a gentle sloping shape.

Gail E. Ferris

October 18, 1998

Image size: 1845x689 pixels.

Weathered thin old paddle found in the loft of the old church. No ridge down the

center, elliptical ends, softly rounded without ridge down the center of the

blade. Such a thin narrow blade is just the opposite of the Kiitdit blade

which I suspect must flex when applied from a standing start. Shaft is

a rounded square.

Overall length: 226cm

Transition to rounded square shaft starts at 85cm

Transition to paddle shaft on the edge of paddle starts at 65cm.

Measured and drawn by Gail Ferris. Dec 4th, 1997.

Gail E. Ferris

I live in Upernavik Greenland where we have a continual parade of

Icebergs. Every time I go paddling I think about icebergs, what

they are doing and what they might do. Icebergs are always

challenging because no two icebergs are alike.

Even though an iceberg may not appear to be quite as fantastic as

the monstrous, tunneled icebergs I have seen in Blomster Bay in

King Oscar's Fiord of Northeast Greenland, still for those of us

who venture on the water in our fragile kayaks, any iceberg is

to be respected. Icebergs can be extremely deceiving, especially

when a big iceberg has done very little for a long time. Then it's

easy to become used to it as just another mountain of ice just

sitting quietly on the water and it don't seem as though it can be

such a threat.

But icebergs are full of surprises and one big surprise can be those

hidden dimensions beneath the surface. The last time I was paddling

decided to make a crossing that would be few miles and to start

from an easily identifiable point. So I choose what simply looked

like two small grounded out bergs. The only thing that seemed just

a little bit odd about these two icebergs is that they were the

only two icebergs side by side and there were no other icebergs near.

It just seemed unlikely but I thought that perhaps the current was

just right at the moment they landed in that bay and then by unlikely

chance happened to have grounded out there together. It didn't really

seem all that likely but I just assumed that anything can be possible

with icebergs.

While I was making the crossing and found myself precariously out

in the middle feeling very vulnerable because refuge was a mile or so

either way, I heard a thunderous crash. And judging from the tone of

the thunder, this was definitely from a large iceberg that was doing

more than just dropping off a few pieces. The sound seemed as though

it could have come down around the bend in another passage. However

the sound could have been an echo from an iceberg that is next to one

of the nearby the cliff faces.

I stopped paddling and carefully scanned all the bergs in sight just

to be sure that there was no steep wave bearing down on me from out of

nowhere. Surfing is nice and I enjoy experimenting with the dynamics

of waves, but as a solitary cold water paddler, I don't like

surprises like being overtaken by a wall of water. I continued the

crossing without any surprises and I just had to make some minor

corrections for current set. I enjoyed looking in detail at the rocks

studying the formations and enjoying the sculptural abstract shapes

of eroded granite.

This is one of those fine moments, which makes kayak paddling such a

pleasure. When you are in a kayak you are experiencing active water

directly and when you are looking at eroded rock you are seeing

what water does to objects that don't move of themselves but

are moved by water. What's unique about an icberg is that it interacts

with the water as a stationary object being eroded and as a floating

object.

But this is only a small part of the spectrum. An iceberg is exposed

to a constant interplay between different temperature stresses. The

entire structure of an iceberg is a product of it's creation with

unequal structural stresses throughout. So you have this constant

shift in dominance of internal structural stresses pieces fall off,

the whole thing splits, the water currents are constantly eroding the

foot, it can ground out and suddenly the center of gravity abruptly

changes and the whole iceberg rolls over. Now you have an entirely

different shape with a new set of internal stresses vying for dominance.

So when it comes to icebergs there is always something happening and

that is what makes icebergs so endlessly fascinating. After I had

enjoyed myself feasting my eyes savoring this unexpected treasure

of abstract forms it was time to head back across the passage. Now

the confusion set in when I turned and scanned the horizon for my twin

iceberg starting point because everything even the twin icebergs

just seemed to blend together. I was looking for distinctive landmarks

on Long Island, which are in the 50-meter range gently rising to a

maximum of 200 meters.

Coming from the opposite side I had been using landmarks such as the

680 meter Umiak Mountain, a valley and long expanse of columnar

basaltic cliffs which are nearly impossible to miss unless it's

hopelessly foggy. On the return the landmarks were so lacking

definition and even the islands melded together making them look

like one massive island. "Wow," I thought to myself; "I didn't

expect this." If I had I would have turned around a few times on the

way over just to familiarize myself what the land looks like as I get

farther and farther away from it. Oops!” I toldmyself "I am usually

more careful than this. You are getting lazy and overly confident."

I calmed myself and started across remembering that I had come on a

diagonal.

All went fine and the two icebergs came into view so I headed for them.

Then just as I was passing them, suddenly there was a huge crash on the

shoreward side where luckily I wasn't. A chunk fell off followed by

more small chunks of ice and I thanked my lucky stars that I hadn't

decided to come in for a landing on that shore because the waves would

have just grabbed my kayak. Such a large amount of ice fell off that the

center of gravity changed. Next the two icebergs revealed themselves to

actually be just one large berg joined beneath the surface by a bridge.

The end nearest me reared out of the water then rolled part way back

under the surface until the berg restabilized on it's new center of

gravity. Now I realized that this berg was easily more than three

times the original size of what I thought it was as two small bergs.

I was glad that I hadn't passed by on the restricted shoreward side or

any closer than I was. I usually carefully decide on the danger limit

of a berg by its size.

This time I had been tricked and I rethought about my original

assumption. One thing that is definite; never assume anything about

icebergs.

Gail E. Ferris

October 18, 1998

Now, that you've come through the thing show here, let us return to where it all started: the bias towards aircraft, that seems to connect a few baidarka builders. In my introduction I already gave you a few hints about hidden aircraft parts in this show.

The question: what do you think is the total number of different homebuilt aircraft, which are shown totally or of which parts are visible within this show?

The answer is on the bottom of this screen.

The frame features only two separation points per gunwale, which means that it can be competely disassembled and then the gunwales split into three pieces each. This results in a very strong frame; the drawback is an increased weight compared to the original. The advantage is an unprecedented mobility for a baidarka.

The empty ''Nevermore'' baidarka is 5.16m long (with rudder 5.30m), has a beam of 55cm and weighs 26.5kg (without sail). The whole expedition equipment are two bags of 32kg and 20kg. About $200 were spent for the skin; $70 for aluminum tubes and scrap plates. Expect to spend a lot more on tools and rivets... The new structure is quite as stable as a rigid boat; but do not expect wonders, because after reaching the point of maximum stress, aluminum will easily give and bend. Compared to a wooden boat, there is always a smaller safety margin, because the fibers of high grade wood seem to be a lot stronger.

I completely redesigned the waterlines; they should be as similar to the original baidarka as possible for a foldable version, which features only one stringer. The ''Nevermore'' is 5.16m long and has a beam of 55cm. At the time, I can only provide you with sketches of the most important parts, especially the four ''gunwale spreader frames''. This is because the other frames are interpolated directly into the structure. You should check David Zimmerly's book; that's where I got the data from.

Anyhow, should you prefer building a wooden folding kayak, I would suggest talking to my brother who has built an extraordinary masterpiece of a folding Greenland Eskimo Kayak. I have enclosed several prints of his boat here.

The output of this action is a boat's beam, length, sheer and rigidity against vertical loads. Combined with the given height of any section, this also predefines the boat's amount of rocker. The two gunwales are designed so strong that they can accept all vertical loads that bear on the structure. This is done with two aluminum tubes and stiffening shear plates that creates an efficient and lightweight shear webbing. The next step is to set up the deck stringer and cockpit rim; now this defines a sort of a ''deck frame''. This approach's advantage is the simple building bed (you may just take some sawhorses); the aleuts also built the ''deck frame'' first. The height of the frames and the position of the stringer result out of David Zimmerlys book ''Qajaq: Kayaks of Siberia and Alaska'', page 17 (Aleut Kayak, collected on Atka Island in 1934 by M.Lantis).

If you consult an aluminum structural handbook you will find that compared to wood, aluminum is not necessarily lighter and stronger if you do not change the construction details. I added to the height of the gunwales and the height of the sheer. I designed only one stringer and placed it at about the middle of the two lower original stringers.

Resulting out of the reduction to 6 frames, the large cockpit, and all that Make-It-Foldable-Stuff there is not much left of the original design of a baidarka. Anyhow, for me it is important to realize the idea of such an old design, even if my realization of it is foldable and of aluminum.

The 3-dimensional form of the boat directly results out of the bending of the gunwale tubes, constrained by the already mentioned four gunwale spreaders. Out of this I measure the dimensions of each frame. There are four frames left to make; 2 for the front and 2 for aft. Actually, I cut them out of 2mm aluminum plates. After all, I disassemble the boat and reinforce all frames. I add the tube connectors and after that, I cut all tubes apart. After cutting, the 3-d form changes a bit, because of the changed material stiffness at the position of the connectors. The boat is cut in two areas; so each stringer has three parts. One separation point is before the cockpit, and the other aft of it. At the position of maximum bending moments (the cockpit area), there is no connector that can break. The bag for the parts is about 1.7m long, 0.25m wide and 0.35m high.

I keep receiving questions about making PVC skins and thus have re-edited my comments about it into a single file that is a little easier to read. Now you see a mix of four years old comments with very recent ones.

Questions and comments by others are printed in blue.

The images are clickable and lead to the full-size (original) pages.

[ Skin Material ]

[ Welding ]

[ Skinning Sequence ]

[ About Tape on a Final Skin ]

[ About Temporary Skins ]

[ Lacing Skins ]

[ George Dyson's Hypalon Skins ]

[ Thomas Yost's Hypalon Skins ]

[ Epilogue ]

In short, the idea about glueing PVC is to use lots of thinner (Acetone). I had to test the mixture several days and came out with that it is right when the thinned glue begins to run off the brush by itself. Then apply it minimal two times to both surfaces. After letting the glue get nearly dry, combine the two PVC parts and press them well for some minutes.

For the first prototype I sewed two strips of PVC onto a zipper

and glued these zipper strips at the middle of the deck piece. This feature

was as strange as convenient;

it eased assembly and loading of the boat.

For the first prototype I sewed two strips of PVC onto a zipper

and glued these zipper strips at the middle of the deck piece. This feature

was as strange as convenient;

it eased assembly and loading of the boat.

With some grief I dropped this idea and the actual design now has hatches

instead of the zipper. These hatches serve the same purpose except that

it is a lot more difficult to assemble the boat. Also I do not have these

sponsons any more that had to stretch the skin.

Anyway, the www site of STAMOID is http://www.stamoid.com/stamoid or http://www.forbo.com and they have some property sheets about that specific skin material.

The skin comes in doublesided or singlesided PVC covering on a polyester fabric. singlesided weighs 280grams/square meter, doublesided is 430g/m2, tensile strength is better than 1200N over 5cm width.

The singlesided stuff is covered with a dirt protecting finish, which makes glueing and welding impossible and thus has to be removed in the contact area.

Paul Raymond wrote: I stopped at a canvas store today, and he sold me 17 feet of double sided Stamoid for $100, which I think is a good price. Since this is for an aluminum folder, and Hendrik Maroske used it with success, hopefully I will too. I'll find another use for the pack cloth.

Stamoid is what I have used, it comes in both protected and unprotected versions. I suggest to get the thinnest material available, that is, I got the 0.6mm stuff and found it too heavy when glued together, so I talked my supplier into buying 0.5mm stuff for me. There even seems to be 0.4mm material out there, and a way to get material with defects (holes) in it (lots cheaper). This material is so thin compared to my Klepper, how does it hold up on your boats compared to commercial boats? Do you still prefer Stamoid to any other material available?

My most recent Baidarka still is the one from the 1999 Toronto trip. The Baidarka skin was finished late summer 1998 and I must confess I did not use the boat very much since Toronto. I have moved the workshop since, and with it the boat, and since that move the lake is a little more difficult to get to (without car).

Anyway, the pics on this website with several closeups of that particular skin have been made during Christmas holidays January 2002, so you have a guess at how good the skin actually is. It still looks "new enough", is tough as ever and still waterproof. No seams broke.

The skin is nearly four years old, the "unprotected" Stamoid, and ready to go on any trip. I'm satisfied with it. Always cleaned stains before they could wear in (with water only), because without the protection I am afraid to use chemicals to clean the skin.

I see that Tom Yost used polyester material, and then coated with hypalon, which worked well for him, but I wanted to avoid having to use toxic coatings, and the pvc material seemed quicker to skin.